"Expanding the transactional-transformative paradigm"

Leadership Research by

Dr. David A. Jordan

President, Seven Hills Foundation

Chapter Four

Here is a very partial list of new metaphors to describe leaders: gardeners, midwives, stewards, servants, missionaries, facilitators, conveners. Although each takes a slightly different approach, they all name a new posture for leaders, a stance that relies on new relationships with their networks of employees, stakeholders, and communities. No one can hope to lead any organization by standing outside or ignoring the web of relationships through which all work is accomplished.

Margaret Wheatley (1999)

Findings

Introduction

Chapter 4 is comprised of three sections. The first section presents findings, drawn from

12 discrete categories of data, concerning emergent themes evidenced by healthcare professionals who are perceived to be transcendent leaders. Key characteristics and affiliated attributes among the study participants are presented. Section two compares the leadership characteristics evidenced by the study participants with those attributes broadly associated with the transactional-transformational paradigm. By describing the leadership dynamic of the study participants discernible differences were noted between the perceived transcendent leaders and extant constructs of transactional and transformational leadership. Noteworthy variances suggest certain descriptive factors specific to the transcending phenomenon. Section three seeks to respond to the final research question of this study, "Is it reasonable to propose a transcending leadership construct?", by comparing the findings evidenced in research questions one and two with propositions posited in the literature concerning transcending leadership. Viewing the research findings through the lens of multiple theories and propositions presents an opportunity to speculate on the reasonableness of the transcending leadership phenomenon.

In reviewing the descriptive findings of this study, it is useful to consider the gestalt of

the study participants. By examining the personal backgrounds of the participants, along with the organizational context in which they are imbedded, the reader is offered a rich understanding of the "lived experience" each healthcare leader presents. A cursory description of each study participant's personal and professional background, along with organizational context, is provided in Appendix H: Study Participant Background and Organizational Context.

In addition to the retrospective self-reports obtained through semi-structured interviews,

corroborative information was sought from informed collaborators. Chemers (1997) notes that without confirming evidence, such as "observation of leader behavior, measures of productivity, or reports by subordinates [or others]" (p. 82), confidence in the study of the leadership phenomenon is suspect. The self-reports of the study participants (SP), herein presented, have therefore been vetted with the reports given by their respective nominating-corroborators (NC) and have been found congruent. Appendix N (Nominator-Corroborator Essence Descriptions of Perceived Transcendent Leaders) offers anecdotal commentary expressed by the nominating-corroborators. These rich depictions are intended to further illuminate the personal and leadership characteristics of their respective nominees.

Findings Regarding Research Question 1: "What are the key characteristics of healthcare professionals who are perceived to be transcendent leaders?"

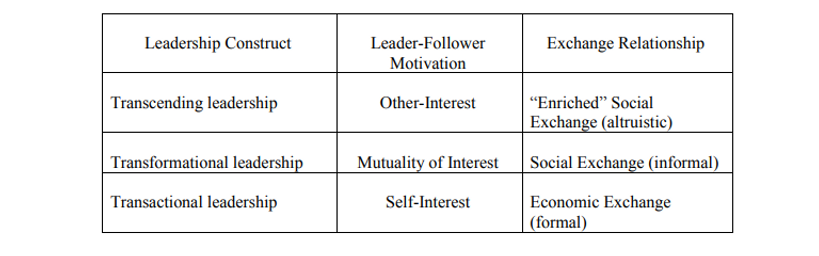

The findings regarding research question 1 (R1) suggest that the perceived transcendent

leaders in this study broadly evidence three key characteristics. These include: "other"-interest, a pronounced orientation to serve the legitimate needs and aspirations of others and broader social causes, without requite. This desire to serve transcends self-interest of mutuality of interests; determined resolve, a committed resolve to pursue goals intended to contribute to the well-being of others, of community, and of broader social purposes; and personal and social aptitudes broadly consistent with emotional intelligence, a pronounced capacity for recognizing and effectively managing one's feelings and relationships with others (Goleman, Boyatzis, & McKee, 2002). Table 14 (Summary findings concerning R1: "What are the key characteristics of healthcare professionals who are perceived to be transcendent leaders?") offers a summary of the findings associated with research questions 1. A proffered definition of each characteristic, as gleaned from an interpretive analysis of the study participant responses, is offered along with affiliated attributes to each.

Table 14

Summary findings concerning R1: "What are the key characteristics of healthcare professionals who are perceived to be transcendent leaders?"

As a means of exploring the genesis of the findings associated with research question 1, a

review of the significant categories of data elicited from the study participants is useful. The resulting affiliated attributes inform the aforementioned three key characteristics and further contribute to a broader understanding of the lived experiences of the study participants.

Category of Data #1: Personal Background and Organizational Context

A composite sketch of the nominated study participants reveals an individual -

overwhelmingly male (n=12) - with an average age of 55.5 years. Each has been married for an average of 29.5 years (n=13) and has three children (n=14). The composite study participant has an advanced degree beyond the bachelors level (n=13) and is either the chief executive of his or her respective organization (n=13) or serves in a significant leadership capacity (n=1). Organization types ranged from an individual family practice (n=1), group practice (n=2), large health system with a budget of $350M or more (n=5), moderate to small hospital system with a budget less than $350M (n=4), and, finally, state-government affiliated health oversight organizations (n=2).

A notable theme expressed by many of the study participants was the value ascribed to

their "family life" and its importance in shaping their "professional lives". One study participant expressed this sentiment noting, "I have been married to my wife for 46 years. [We have] three children and three grandchildren. We have a family dinner of four generations every Sunday. That's the prize of it [my professional and personal success]" (SP4). Another stated,

My background is Cuban American, my parents were Cuban refugees, they're both passed away, and I'm the oldest of eight kids. I'm married and have five children of my own and am titular head of my large extended family. Family is everything and then comes the work. (SP5)

A third participating leader added, "We're a very close family, that's been great. I couldn't have asked for anything more in my family. It's always been the first priority, despite the demands of my job" (SP6).

When asked about hobbies or avocational interests, many of the participants mentioned

reading biographies, travel, and physical activities such as golf, hiking, and exercise. The reference to the value of physical exercise in the lives of the study participants is summarized by one of the leaders:

I swim each morning; we [my wife and I] try to stay in good physical shape. We do some kayaking, reading, and a lot of travel. You have to stay in measurably good physical shape in this [healthcare] field. These are hard jobs to do unless you have good fitness and stamina - both physical and mental resilience. (SP12)

In general, the study participants credited a notable rich family life, and to a lesser degree, their avocational interests in supporting their professional pursuits. One discrepant perspective was that of a CEO of a large urban/suburban healthcare system. When asked, "What do you enjoy doing outside of work?", he commented:

Well, there isn't much I do outside [of work] because I work pretty much all the time. I don't take an awful lot of vacations. I wouldn't consider myself a crazy workaholic, although some would define me as that. But, I don't consider it as work; I just love what I do. (SP13)

In summary, the study participant's leaders were in their mid-50s, held advanced degrees

in medicine, healthcare administration, or related fields, and assumed senior leadership roles within a diversity of healthcare organizations. They came from various regions of the United States and lead organizations in rural, suburban, and urban settings. A significant theme that emerged among the study participants was the degree to which the majority of leaders (n=12) voiced the significance or a stable and rich "family life" as being integral to their perceived success as leaders.

Several additional questions were posed to the study participants as a means of gaining

further insight into the essence of each individuals and how contributing factors impact the leadership dynamic. Inquiry into each participant's core personal values and existential/spiritual beliefs contributed to a greater understanding of the essence that defines these healthcare leaders.

Category of Data #2: Core Values

Several scholars have contributed to the discourse on the praxis of individual values and

the leadership phenomenon (Bean, 1993; Bennis & Nanus, 1997; Blanchard & Peale, 1998; Clawson, 1999; Covey, 1991; Deal & Kennedy, 1982; England & Lee, 1974; Finkelstein & Hambrick, 1996; Huey, 1994; Hunt, Woods & Chonko, 1989; Kennedy, 1982; Kilcourse, 1994; Kluckhohn, 1951; Kouzes & Posner, 1993; Kuczmarski & Kuckzmarski, 1995; Massey, 1979; and Russell, 2000). Rokeach (1979) suggested that individual values are "socially shared conceptions of the desirable" (p. 48). That is, values serve as a set of beliefs that help govern our actions and our expectations of those individuals and institutions with whom we share our social milieu. Hunt, Woods, and Chonko (1989) asserted that "values help define the core of people. They help explain why people make sacrifices and what they are willing to give up to attain goals" (p. 80). Rokeach (1979) noted that,

Values served as standards that we learn to employ transcendentally across objects and situations in various ways: to guide action; to guide us to the positions that we take on various social, ideological, political, and religious issues; to guide self-presentations and impression management; to evaluate and judge ourselves and others by; to compare ourselves with others, not only with respect to competence, but also with respect to morality. (p. 48)

Burns (1978) would posit a framework of values: modal values as modes of behavior (e.g., honesty, responsibility, courage, fairness to others, etc.) and end values as goals and standard (e.g., social equity, justice, human rights, etc.) which, when evidenced in the actions of a leader, contributed to "higher stages of moral development" (p. 429) in the leader, followers, and the broader society.

Personal values are internalized so deeply that they define personality and behavior as well as consciously and unconsciously held attitudes. They become an expression of both conscience and consciousness. Hence, holders of values will often follow the dictates of those values in the absence of incentives, sanctions, or even witnesses... (p. 75)

Given that Burns (1978) and notable others have averred the importance of core personal

values as defining variables in understanding both leaders and the leadership phenomenon, each study participant was asked, "What are your core personal values... what do you stand for, what do you hold most dear, what directs your actions?" These questions elicited a broad range of responses. In total, 19 separate values were cited by the participant leaders. These 19 core values were conflated into 7 broad themes representing 3 modal, or behavioral values (i.e., respect for family and community, honesty and truthfulness, and doing the right thing); 3 end values, representing desired goals (i.e., fulfillment of personal/professional obligations, personal integrity, fair treatment and equity toward others); and one value (i.e., service to others) which is construed as a unified value in that it evidences both a behavior and desirable social conception. Table 15 summarizes the thematic responses in order of frequency.

Table 15

Thematic responses of study participants re: Core Values

The most frequently noted core value theme was "respect for family and

community". Respondents described this value in various ways:

"I have made statements to people that you should be true to... your family and

community. [Your family] and your community is very, very, important and you should put those values and those relationships above your career" (SP7).

"Family is THE value. It would have been hard to not have a job that fit with my family's

life" (SP6).

I think my mother served me well as a strong leader. She always said whatever you are doing, whatever it is - playing, school, work, whatever, do it the very best you can, do it well. But one other statement she added... she said, "whatever you participate in, whether it's long or short, make it better than when you came." And so my mother and my family have been instrumental to me in articulating my own core values. (SP2)

Secondary to a pronounced affinity for "family and community" the participant leaders

identified the unified end value/modal value of "service to others" are the most cited core value. This value was expressed in various terms, yet evidenced the earnest desire to actively contribute to the well-being of others. One individual noted,

My core values? Obviously my family is going to be up at the top... and also a strong value of giving back [to the community]. Having grown up in the 60s, it would be hard not to be touched by that era and [the importance of] making a difference and giving back. And I think healthcare appealed to me because of that. Those are some of the values that I think I stand for... family and service to others and community. (SP12)

Study participant 1 further exemplified this sentiment,

I think service [to others] is number one. From childhood, probably because of my grandfather's influence, service has been pounded home to me by my father, along with his brothers and sisters. We had a huge extended family and we would get together on holidays and there were always a couple of ministers in the family and almost everybody, one way or another, was involved in a social service... it was always placed in front of me as a young man that therre was not a better position in life than to be of service to your fellow man. (SP1)

The responses elicited from the study participants suggested that the wellspring from

which their core values were shaped began early in life and were influenced by a variety of factors, such as family history, cultural background, the influence of key mentors and related factors. This perspective is consistent with a body of previous research. Massey (1979) suggested that personal values are shaped through inter and intrapersonal influences such as family, friends, religious beliefs, education, cultural background, and seminal social events. Kuczmarski and Kuczmarski (1995) would further refine this assertion in specifying four factors, which instigate value formation: family and childhood experiences, conflict events that evoke self-discovery, major life changes and experiences, and personal relationships with important individuals. Finkelstein and Hambrick (1996), attempting to add further clarity to this thread of reasoning, suggested that personal values are shaped within a social context; therefore, they may be influenced by cultural forces, social organizations, and family. Stipulating that the familial, cultural, experiential, and the influences derived from significant others or institutions are apposite in shaping a leader's core values, Russell (2000) stated:

Values significantly impact leadership. Personal values affect moral reasoning, behavior, and leadership style. Values also profoundly influence personal and organizational decision-making. The values of leaders ultimately permeate the organizations they lead, shaping the culture through modeling important values. Ultimately, values serve as the foundational essence of leadership. (p. 64)

A reflection on the core personal values of the study participants - their "conscience and

consciousness" (Burns, 1978, p. 75) if you will - along with contextual information on each of their personal and leadership backgrounds adds to a growing insight as to the nature of each individual. A further perspective that may contribute to an understanding of the participant's leadership experience is the degree, if any, to which each attributes a spiritual or existential motive to their work as a healthcare leader.

Category of Data #3: Spiritual/Existential Influence (s)

Associating individual spirituality with the leadership phenomenon has elicited the

interest of a growing number of scholars. Hall (1984) attributed, "leadership development with spiritual maturity, suggesting that highly developed leaders are those who view the world as a sacred mystery" (In Marinoble, 1990, p. 5). Ritscher (1986) posited that genuine leadership acknowledges and nourishes the spiritual nature of followers while Fairholm (1998) has suggested that a leader's spirituality is inextricably linked with the values and behaviors they exhibit in the workplace. To add to the discourse, Maslow (1999) asserted that, "the human being needs a framework of values, a philosophy of life, a religion, or religious surrogate to live by and understand by, in about the same sense that he or she needs sunlight, calcium, or love" (p. 226). Therefore in order to peer further into the lived experiences of the study participants, it is useful to consider their spiritual or existential beliefs in context to their work as healthcare leaders.

When viewed in their entirety, the study participant responses did not suggest any

discernible theme or proclivity advancing the notion of a meaningful correlation between the leadership phenomenon and a leader's sense of personal spirituality. Among the fourteen respondents, four (n=4) of the leaders felt their spiritual beliefs were a defining influence in both their personal lives and leadership roles (SP2, SP7, SP9, and SP10); six respondents (n=6) expressed only a moderate affinity to spiritual or existential beliefs (SP1, SP3, SP5, SP6, SP8, and SP10); while four study participants (n=4) did not personally identify themselves as having an influential spiritual conviction (SP4, SP11, SP12, and SP13). Table 16 summarizes the responses of the participant leaders as to the degree each purported to be influenced in their work as healthcare leaders by spiritual or existential beliefs.

Table 16

Influence of spiritual/existential beliefs on the work lives of perceived transcendent leaders.

Reflecting the opinion that their spiritual beliefs had a significant correlation to their

work as healthcare leaders, the responses of SP9 and SP10 are informative. "My values and my Christian faith are essential to who I am as an individual and that cannot be separated from my work" (SP9). "After high school I spent nine years as a member of a religious community as a Franciscan sister. God and prayer are very important to me. I feel that's a part of my being" (SP10).

A more temperate association between their spiritual beliefs and work lives are exampled

in the comments made by study participants 1 and 3. Study participant 1 noted,

Well, I have an earnest belief in a higher authority, God. I'm also a scientist, a physician, who deals with the realities of life in sometimes stark terms. With that said, I supposed my beliefs integrate both the spiritual aspects of faith along with existential notions of man's role in the cosmos. Each inform the individual I am and therefore my role as a healthcare practitioner and leader, but they don't predetermine, nor overly guide my actions. (SP1)

This moderate view is also advanced by study participant 3.

I suppose it's defining in the sense of - I don't understand how a physician cannot believe in God. It seems quite impossible, having been a practicing physician for as long as I have and having seen so many things that I know I did not affect. So that's an underpinning, [but] it does not direct my day-to-day thinking. I would say being a woman affects my day-to-day thinking much more than my religion. (SP3)

In contrast to those respondents who noted that spirituality was a defining influence in

their personal and professional lives, three study participants (n=3) were certain in their opinions that spirituality had marginal to no effect on their personal or work responsibilities. The sentiment is evidenced in the responses of two leaders, SP4 and SP13.

I'm not religious; I'm secular. My thinking is more closely aligned with existential thought. I believe there are forces within the universe, which create wonderful, and unique symmetry and that we as a species are continuing to grow and change. (SP4)

Study participant 13 added, "I'm not terribly involved in organized religion... I do think you were put on their earth to make things better, but I'm not a spiritual person" (SP13).

Finally, one respondent (n=1) expressed angst and exasperation in confronting the

question of his spiritual or existential beliefs in stating, "I don't know what I believe! I was raised Catholic through grade and high schools, but then it rubbed off" (SP11).

In summary, no significant or invariant themes concerning the spiritual or existential

beliefs of the study participants were noted. Their individual beliefs were reasonably distributed among three stipulated degrees of influence (see Table 16). Physician leaders and health system leaders were evenly divided among the four respondents (n=4) who felt their spiritual beliefs were a defining influence on their work. In contrast, only one physician leader (n=1), as opposed to three health system leaders (n=3), noted that their spiritual/existential beliefs had little to no influence on their work.

A cursory insight into the study participant's personal background, the organizational

contexts in which they lead, core personal values, and finally the degree to which each identifies and associates their spiritual or existential beliefs with their roles as leaders establishes a useful foundation from which to examine the lives of perceived transcendent leaders. Additional categories of data further this phenomenological inquiry and suggest significant themes that inform research question 1 (R1) of this study.

Category of Data #4: Career Highlights Self-Reflection

When asked, "What are you most proud of in your career?", the participant leaders offered responses, which could be broadly categorized within three general themes: family, culture creation, and legacy. Table 17 (Career highlight themes of perceived transcendent leaders) illustrates how participant comments were recorded.

Table 17

Career highlight themes of perceived transcendent leaders

"Family" themes were so recorded if the respondent specifically identified family relations as their principal career highlight; even though this response may appear to be only tangentially related to career. The comments noted by study participants 4, 10, and 11 were indicative of four participant leaders (n=4) who noted "family" as their career highly. "Obviously, I'm most proud of my children, no question about it... far and away that's the first. My husband and I have been lucky" (SP10). "[I'm] proud of my family before anything else. I'm proud of the communication that I have with my wife and kids" (SP11). Study participant 4 epitomized the essence of this theme in stating,

I am most proud of my family. They are great people and we have fun together. I've seen many "great people" who family life is in shambles, and I feel sorry for them. I can talk about a lot of things in life [I've accomplished], but what is dearest to me is that we have a good family. (SP4)

The second theme which emerged when questioning the study participants about a

moment, an action, or event which they felt most proud of in their careers, was the effect they believed their leadership had on establishing or furthering a positive "culture" within their organization. By culture, the respondents variously referred to the "atmosphere", "ethical culture", "cultural values", and so forth. The responses provided by study participants 6 and 12 serve to illustrate this sentiment.

I take great pride in [my organization] because it's a place that has moved from a naïve idyllic little [medical] college that loved teaching and all these great values to a fairly sophisticated business that still has all those cultural values. I feel I am as loyal to the founding values of this place as were the first directors. (SP6)

They are not moments, or events, or programs that I started, although I could list a lot of those, but I guess what I'm most proud of is the culture that we've created. I would like to think that [my organization's] culture is a very strong ethical culture noted for its quality and service to the community. (SP12)

Finally a third theme, which emerged in response to this category of data was mention of

specific services or programs the healthcare leader introduced and believed would establish a lasting "legacy" of care for others. Statements offered by study participants 3, 8, and 13 are noted below as examples of this significant theme.

I guess I would change "proud of" to "most personally satisfied". I was part of a 12-year project rebuilding a medical curriculum at King Abdullah Medical School in Jetta, Saudi Arabia and establishing a dental school and making plans for a public health school there. I was sent as the leader of the project by my university [Tufts], which absolutely stunned the Saudi's because they never considered that anyone would send a woman to lead such a project. Learning how to politically navigate a very different culture, I think was personally the most satisfying project I have completed. (SP3)

Study participant 8 added to the "legacy" theme in noting,

We opened four rural health clinics, which gave access to healthcare to people that if you looked at the statistics, were just deplorable for - you know, the wealthiest country in the world. So maybe it's the health outcomes [I'm most proud of]. It's nice to be able to look back in your career and say you've left your thumbprint somewhere. (SP8)

Finally, a career event, which has resulted in a broad social benefit, was identified by participant leader 13:

What I was most proud of in [my career] was I was one of the architects of a managed children's healthcare program... The Childhealth Plus Program that became the model for the national CHIPS program. Looking at something tangible, that kids have gotten healthcare they otherwise wouldn't have got, it makes me feel good. At the end of the day, that's what it's all about. (SP13)

In summary, when each of the study participants was asked what they were most proud of

in their career, three themes emerged; family success, establishing a positive organizational culture, and creating a lasting legacy. Each of these themes were reasonably divided among the fourteen study participants with creating a future legacy the most frequently mentioned (n=6). It is noteworthy, however, that a consideration for the primacy of "family" has been further evidenced augmenting the commentary expressed by the participants in earlier categories of data. Inquiry into the participant leawder's career highlights gives rise to the retrospective influence that life experiences may have on their current view of leading and collaborating with others.

Category of Data #5: Influence of Life Experiences on Leadership and Collaboration

The experiential basis(es) from which the study participants have formed their

fundamental beliefs and values concerning leadership and collaborative behavior serve as a further descriptive device in understanding the leadership experience of the respondents in this study. When asked, "How have your life experiences influenced you views on leadership and, in turn, how do you collaborate with others?", two driving influence themes and three collaborative behavior themes emerged. Driving influence themes, which were significant in shaping the respondents views on leadership included: family history experiences and work history experiences. Resultant behavior noted by the fourteen study participants were then analyzed and summarized as three collaborative behavior themes including: self-reflective action, empowering and involving folllowers, and committing to serving others and community. Table 18 summarizes the life experience driving influence themes and collaborative behavior themes noted by the study participants.

Table 18

Life experience drivers influencing leadership resultant collaborative behavior(s)

Corroborating what has been evidenced in the categories of data reviewed thus far, the

influences of a personal family history appears to have a significant impact upon the study participant's conception of leadership and their collaborative behaviors. Results noted in table 18 (Life experience drivers influencing leadership and resultant collaborative behavior) indicated that, of the fourteen respondents, ten (n=10) noted that their past family experiences was the preeminent driver effecting their present sensibilites concerning leading and collaborating with others. This sentiment is most clearly expressed by participant leaders, SP5, SP10, and SP14.

Watching my parents [as Cuban Americans]. They emphasized the value of looking at things from different perspectives, take the same thing and then look at it from someone else's perspective, or from outside yourself... I collaborate very effectively with people who have lots of confidence and who are capable in whatever capacity. If you don't have a lot of confidence or have an ulterior motive, then people have a lot of trouble dealing with me. (SP5)

Study participant 10 added:

I believe we're all products of the road we've taken. I have five brothers - we grew up in a blue-collar family, so it was a family that was very tight. We didn't have a lot, but that begins to lay a foundation of [hard work]. We saw our parents work hard and I think that gave me a strong foundation. So, a foundation of hard work and a sense of spirituality was part and parcel of my [upbringing] and influences today how I view leadership and how I collaborate with people. (SP10)

Tangentially related to a personal family history, one respondent drew upon his family heritage as a driving influence in shaping his leadership sensibilities. He noted, "My Native American heritage has given me a platform to understand leadership. And so, I'm heavily invested in work groups and teams" (SP14)

Study participant 9 epitomized the responses of the four responding leaders who

identified past work experiences as the primary driving influence effecting their views on leadership and collaboration.

My work over the years has taught me that leadership is removing the barrier so people can do their jobs and succeed, relating to workers as real people with their own human needs and helping them grow as professionals and people. [Regarding collaboration], effective leadership has to be personal, as well as professional. All of us in this organization are caregivers to each other. (SP9)

Collaborative behavior themes which expressed themselves through family and work

history experiences included self-reflective action, empowering and involving other, and committing to serving others and community. The former theme (i.e., self-reflective action) was graphically expressed by study participants 1 and 3. Study participant 1 noted,

One of the first elements of leadership I recall was my uncle... he was enthusiastic and sincere and showed me that leadership is a multi-faceted thing and that you have to be sort of vulnerable. You have to have faith that what you'res saying is going to be grasped by people if you just go at it hard enough. Everyone who wants to lead has got to project [their own] leadership qualities. And that projection is based on an understanding of yourself and what your strengths are - and it's got to be based on the truth; the trust of the message you're sending; the truth of what you're involved in doing. (SP1)

Recognizing personal foibles as a means of identifying opportunities for personal growth was expressed by study participant 3.

Well I guess in any leadership position that you find yourself in... you have to recognize what your weaknesses are and then make up [for them] by developing strengths. In every different position that you have, you will find a new set of weaknesses, either your own, or because of the structure, or political situation, or whatever, and I think the key to success in leading and collaborating is figuring out how to turn those weaknesses into strengths. (SP3)

The second behavioral theme identified, empowering and involving others as the

foundation to collaboration, was noted by five respondents who variously described this theme. Study participant 11 noted that he leads and collaborates with followers through a process of "collective team spirit, creating confidence within a group, and creating an atmosphere of fun".

The final collaborative behavioral theme which presented itself as a manifestation of the

life experiences of the study participants was in personally committing to "serving" others and community. Study participant 4 captured the essence of this theme in stating,

The only thing constant throughout all of [my] forty years of work is my commitment to serving my community. It's been an evolution. Whichever community I'm in - be in Chinatown, my family, my extended family, my patients, that commitment to be helpful and to work with people - to serve people - to move forward. To serve the needs of othersr first is the best way to collaborate. (SP4)

In summary, category of data 5 sought to describe how life experiences may have

influenced the study participant's views on the phenomenon of leadership and collaboration. Two driving influential themes emerged; family history experiences (n=10) and work history experiences (n=4). In turn, three collaborative behavior themes presented themselves: self-reflective action, empowering and involving others, and committing to serving others and community. The significance of family history and its apparent influence on the leadership phenomenon - as evidenced in the lives of the participant leaders - suggests the emergence of an invariant theme in the study of perceived transcendent leaders.

Findings associated with categories of data 1 through 5 suggest certain themes offered by

the study participants relative to their self-reflective beliefs, values, and experiential factors which influence their personal and work lives. Drawing reference from a more impersonal context, respondents were asked to speculate on the essential traits required of today's healthcare leaders.

Category of Data #6: Perceptions of Essential Leadership Traits

As noted in Chapter 2 (Review of the literature) of this study, articulating and promoting

specific traits describing the leadership phenomenon has been problematic. In the mid-1900s, Stogdill (1948) initiated a meta-analysis of existing trait research and concluded that, "A person does not become a leader by virtue of the possession of some combination of traits" (p. 64). Rather, he determined that situational factors in combination with certain leadership traits more accurately defined the leadership phenomenon. In a follow-up study Stogdill (1974) reaffirmed his assertion that both personality traits and situational factors were key determinants in describing the leadership phenomenon (Northouse, 2001, p. 17). More recently Kirkpatrick and Locke (1991) have asserted that "traits alone, however, are not sufficient for successful leadership - they are only a precondition. Leaders who possess the requisite traits must take certain actions to be successful. Traits only endow people with the potential for leadership" (p. 49). Suffice it to say, research describing how traits - as one of several key characteristics - may influence leadership is ongoing.

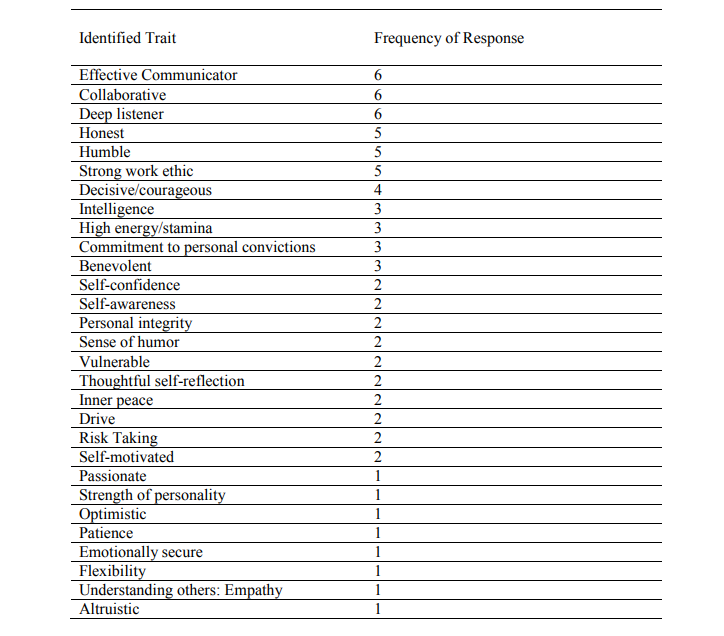

Stipulating that identifiable traits may contribute to the mosaic of the leadership dynamic,

the study participants were asked, "What do you feel are the essential traits necessary for leaders in healthcare today?" In total 76 responses were elicited represented 29 unique trait descriptors. A listing of these responses in order of frequency is presented in Table 19.

Table 19

Leadership traits identified as essential to healthcare leaders.

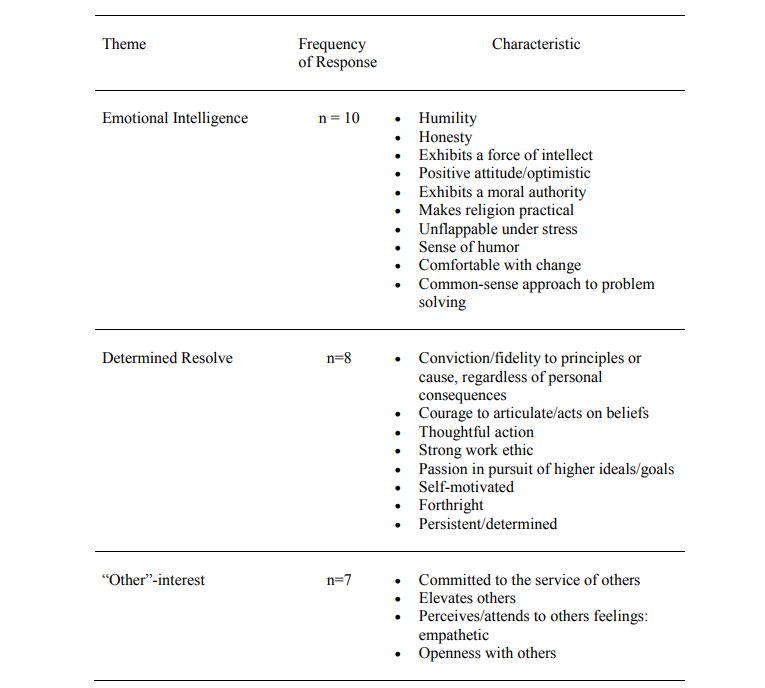

In reviewing the various traits suggested by the participant leaders, several significant themes emerged. These trait themes are identified in Table 20 and may be summarized as emotional intelligence, "other"-interest, and determined resolve.

Table 20

Trait themes identified.

These three trait themes became evident after repeatedly analyzing and combining the trait variables into clusters that appeared to be congruent or share similar features. In turn, these clusters of traits emerged as groupings whose core elements could be readily identified with: an orientation to others, a determination of effort, and finally - drawing from Goleman, at al. (2002) - the domains of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, and relationship management which are broadly associated with the theory of emotional intelligence.

The most common theme identified is conceptualized in terms of emotional intelligence.

Characteristics such as patience, honesty, humility, inner peace, self-reflection, and integrity exemplified participant leader responses. One study participant offered this sentiment concerning integrity as an example of emotional intelligence. "I think integrity has to be critical. Personal integrity that goes beyond your own interpersonal relationship must be a fundamental trait. It's about being a fair player and being honest with yourself, as well as the people you relate to" (SP2).

The significance of emotional intelligence was further evidenced in attributes such as

self-awareness, self-confidence, and a sense of humor. Study participant 9 succinctly catpured the essence of this theme noting,

I would say three things - one has to be some degree of self-awareness. People have to know what they believe. They have to be able to describe themselves and be able to articulate their organizing ideas. Secondly, they have to have self-confidence. You run into people all the time who are sort of emotionally, intellectually, psychologically needy- they are defined by others, they don't have enough self-value of confidence. [And third] having some sense of humor; some willingness to not take yourself too seriously. (SP9)

A secondary theme, interpreted as "other"-interest, reflected a notable consideration for

others. Affiliated attributes including empathy, collaboration, benevolence, altruism, and the ability to listen and communicate were noted as essential leadership traits. One participant leader said, "I think you have to be a very careful listener. [Individuals] need to feel that they're being listened to and heard, not just listened to, but appreciated and heard" (SP3). Another stated that she believed an essential trait for a leader is the ability to effectively communicate to others a vision of a possible future.

... an individual who is able to create a vision and then have the ability to communicate that vision. That's what begins to set people apart. It's an individual who can see things in a different way. There are people who can see things but don't always have the ability to communicate it and to energize others to work toward it. (SP10)

Another leader captured the essence of the "other"-interest trait theme in his sentiment,

"the last trait, and the most important I think, is try to find the nugget of goodness in everybody" (SP1).

Determined resolve also emerged as a significant theme. One leader expressed the

following:

You have to be passionate about a cause and believe in it. It may be in... the people you are working with, or the issue of the patients, but you have to have a passion which people identify and you are known for. (SP11)

Courage was a trait noted by several study participants within the broad theme of determined resolve. One participant explained it this way,

A sense of courage - you can be self-confident, but not be very courageous in terms of truth telling or admitting you're wrong or realizing your weaknesses. People who are courageous will articulate their ideas; they'll defend and own them. They will enter into risky places. (SP9)

In summary, three significant themes emerged when the study participants were asked to

identify the essential traits necessary for today's healthcare leaders. The trait themes included, in order of frequency: emotional intelligence, "other"-interest, and determined resolve.

Paralleling an inquiry perceived essential traits the study participants were similarly

asked to identify essential leadership behaviors.

Category of Data #7: Perceptions of Essential Leadership Behaviors

Inquiry into leadership traits provides an insight into those personality characteristics the

study participants felt were essential for today's healthcare leaders. In contrast, discerning key behaviors - "what leaders do and how they act" (Northouse, 2001, p. 35) - from the perspective of the study participants contributes to a richer understanding of how perceived transcendent leaders envision the leadership phenomenon. When asked, "What do you feel are the essential behaviors necessary for leaders in healthcare today", the participant leaders provided 58 responses of which 30 were determined to be unique behavior descriptors. Table 21 provides a summary of the essential leadership behaviors noted by the study participants.

Table 21

Leadership behaviors identified as essential to healthcare leaders.

In attempting to identify significant themes drawn from these responses, those thematic categories previously gleaned from the earlier review of essential traits appeared appropriate. This is reasonable premise in that leadership behaviors are broadly affiliated with manifested characteristics (i.e., traits, values, principles) of leaders (Fleishman, 1978). As such, the behaviors identified by the study participants are noted in Table 22 and comprise three behavior themes: emotional intelligence, "other"-interest, and determined resolve.

Table 22

Leadership behaviors as identified as essential to healthcare leaders.

Behaviors associated with emotional intelligence surfaced as the principle leadership

behavior theme. Maintaining a sense of humor, doing the "right" thing, acting selflessly, and demonstrating humility were among the characteristics cited. A study participant referenced self-effacing behavior this way; "I think any great leader expects much of their followers, but even more of themselves. They show their humility through their humor, [which is] sometimes self-deprecating" (SP1). Remaining flexible in responding to circumstances, being honest, and maintaining moral and ethical control were also mentioned as desirable leadership behaviors. One leader expressed a combination of these behavior characteristics in terms of self-denial, humility, and a willingness to publicly articulate one's values.

[An essential leader behavior is] the element of self-denial. Leaders who don't take all the things they could get. There is an element of humility. [Another behavior] is not drawing attention to your service. So a lack of self-advertising, self-congratulation, which I guess, is humility by another name. Also, a lot of people have beliefs and values, but what sets people apart is their willingness to acknowledge them [publicly]. Humility and remaining ethical in your actions are absolutely required behaviors of healthcare leaders in the future. (SP9)

"Other"-interest was the second most notable behavior theme cited. The compelling

mandate of leaders to exhibit a genuine and earnest concern for the welfare of others - even before self - was a common thread woven throughout the study participant responses. One leader expressed this essential behavior in the context of his own life experiences.

They [admired colleagues and family members] inspired me through their behaviors and actions, they inspired me through the confidence and demands they had on me, and they inspired me in the nobility of their causes - what they stood for that was beyond them. They forcefully pursued the greater good of others, even before their own good. (SP1)

Finally, the theme of determined resolve was aptly illustrated by study participant 12, as

he conjoined the behavioral characteristics of focus and persistence.

[Healthcare leaders] must put the organization first and leave their ego at the door, and really build a culture base with strong ethical values. They should focus on the organization's mission and their vision; where they are heading. They should be the role model for the organization; they walk the talk and set the culture. They should be humble, but extremely driven and focused and tenacious. (SP12)

In summary, three behavior themes emerged as significant when study participants were

asked to speculate on the essential behaviors necessary for healthcare leaders in today's environment. The specific behavior themes noted appear to correspond closely with the perceptions of essential traits noted earlier in category of data 6. They include, in order of significance: emotional intelligence, "other"-interest, and determined resolve.

Adding to earlier categories of data, conceptions on the manner in which the study

participants inspire and motivate their followers contribute additional insight into the essence of the leadership phenomenon as experienced by the respondents.

Category of Data #8: Self-Reflection on Motivating Followers

Much has been written concerning the nature of motivation and the theories intended to

describe it. For the purposes of this study, the definition proffered by Steers and Porter (1991) was presumed when interviewing the study participants; that is, motivation as a set of forces that cause others to behave in certain ways. Study participant responses werre compared to extant need theories of motivation (Alderfer, 1972; Herzberg, 1968; Maslow, 1943; McClelland, 1961; and Murray, 1938) and process theories of motivation (Adams, 1963; Kelley, 1971; Lewing, 1938; Luthans & Kreitner, 1975; McGregor, 1960; Porter & Lawler, 1968; Tolman, 1932; Vroom, 1964) in order to draw any correlation between the responses offered and the general factors associated with motivation theory.

When asked, "How do you inspire and motivate others?" the study participants offered 34

responses. After combining similar remarks, 16 unique motivational techniques remained. Table 23 provides a listing of the summary descriptions.

Table 23

Motivational techniques utilized by study participants.

Among the 16 summary descriptions, two significant motivational themes emerged: affiliation orientation and achievement orientation (McClelland, 1961 and Murray, 1938). Table 24 clusters the participant leader responses as either affiliation techniques or achievement techniques.

Table 24

Motivational technique themes.

Broadly defined, affiliation refers to the need for human companionship vis à vis an individual's desire to gain assurance and approval from others. Individuals who have a high need of affiliation are genuinely concerned with the feelings of others (Schachter, 1959). In contrast, achievement arises from an individual's need to succeed in accomplishing difficult tasks or aspiring to elevated standards of performance. As noted in Table 24, fourteen (n=14) of the motivational techniques cited by the study participants were affiliation oriented, while only two (n=2) were achievement directed. None of the motivational techniques mentioned were considered to be power-oriented, the third component of McClelland's (1961) theory of needs model after affiliation and achievement orientation. This would suggest that the study participants perceived that their followers were broadly motivated by intrinsic benefits. It is noteworthy that not a single study participant response made reference to extrinsic motivating factors (e.g., the offering of money, power, position, etc.) as a motivational technique they employed - or by extension felt their followers desired. For these study participant motivation was broadly envisioned as a function of personal relationship building, manifest in a mutual commitment to an inspiring purpose.

Communicating an inspiring sense of purpose and leading through example were two

notable motivation techniques cited by the study participants. The former is captured by one of the participant leaders.

[I offer my staff] a sense of purpose to what we're doing. We're civil servants, we're not here for the pay. Our satisfaction comes from what we do [which] goes back to caring for our patients. I try to get [my staff] to look beyond what they are as an employee and to see the meaning they have in the lives of other people - that we are making a difference in their lives. I try to instill within them the importance of what they do. (SP14)

Motivating their followers through example of their personal actions was noted by

several leader. One stated, "I motivate and hopefully inspire others by leading by example. I've found that partnership decisions work better than handing down decrees. So decision-making by consensus is how [I like to motivate]" (SP2). Another noted, "... a lot of it is just by [my own] example. I think if I'm excited and motivated, then my staff is, and that rubs off on everyone" (SP8).

Beyond communicating a noble purpose and demonstrating that purpose through

personal example, the study participants offered a variety of related thoughts on motivating others. One particularly compelling assertion emphasized the leaders role in establishing follower identification within the organization.

You have to offer staff a sense of belonging; that they're not just here filling a slot. They belong to something and they can make that thing better if they commit to it - which in turn will make themselves better. People often use financial incentives and other things to motivate; those are not the primary issues, in this business [healthcare] anyway. (SP13)

In summary, the study participants commented on the variety of techniques they utilize in

motivating and inspiring others. Two motivational themes emerged: an affiliation orientation and an achievement orientation. Of the 16 motivational technique descriptors, fourteen were affiliation-orientated. This would suggest a belief on the part of the study participants that followers valued relationship building and other intrinsic benefits over achievement-oriented or power-oriented motivators. In turn, this may also suggest that the perceived transcendent leaders within this study are, or have themselves been, highly motivated and inspired by others who have employed affiliation-oriented behaviors. This finding is consistent with social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), which asserts that human behavior may be learned and/or influenced through observing and modeling the attitudes, emotional reactions, or behavior of influential others. As a means of advancing this thread of inquiry, the study participants were asked to identify individuals, past or contemporary, that they felt embodied extraordinary leadership characteristics (i.e., traits, behaviors, distinguishing qualities, etc.). This deductive approach, juxtaposed to their earlier responses concerning core values and perceptions of essential leadership traits and behaviors, may further illuminate the essence of the leadership phenomenon as experienced in the lives of the study participants.

Category of Data #9: Characteristics Admired in other Leaders

In asking, "Who would you suggest as an individual(s) who best represent your notion of

an extraordinary leader and why?", certain deductions may be reasonably made concerning those leadership characteristics to the respondents, they may serve as a further insight into the mind of perceived transcendent leaders. Table 25 summarizes those individuals identified by the study participants as "extraordinary leaders" along with their associated characteristics (i.e., traits, behaviors, distinguishing qualities, etc.). In total, the fourteen study participants offered 63 responses representing the characteristics of 25 admired leaders. After comparing for similarity in meaning, the 63 characteristic responses were conflated to 25 unique characteristic descriptors.

Table 25

Admired leaders and perceived characteristics identified by study participants.

Consistent with the earlier examination of perceived traits and behaviors, the 25 unique characteristic descriptors suggested three significant themes: emotional intelligence, the leaders determined resolve, and finally, an orientation to others. Table 26 identifies the three signicant theme and corresponding admired leader characteristics, in order of frequency.

Table 26

Characteristic themes of admired leaders.

Emotional intelligence once again emerges as the most frequently noted characteristic

theme. Study participant 6 described this theme in terms of one admired colleague's ability to remain calm in moments of stress.

[name], who is the senior vice dean at Columbia and our Board chair and my mentor. The thing he does is - he's unflappable in times of stress. I get reserved when stressed, but [he] just moves on. He brings all the elements of openness, dialogue, humor, knowledge, and insight to [our discussions]. He cares about people and he is the single most exemplary individual I have encountered in healthcare. If I could just be him when I'm his age; I would be very satisfied. (SP6)

The characteristic theme of emotional intelligence was further exampled in admired

leaders. Study participants described this as expressions of humility, optimism, and honesty. A study participant described the characteristics evidenced in his grandfather, "... he blended American optimism and can-do with honesty and forthrightness" (SP11). Another respondent noted the humility of former US president Harry Truman this way: "He remained humble through everything... he did the best he could [when he was President]. And he was honest with people, almost brutally honest" (SP14).

Determined resolve emerged as the second most frequently noted characteristic theme

identified in the study participant's description of admired leaders. Within this broad theme, "conviction/fidelity to a set of principles or a cause regardless of personal consequence", was the most frequently cited characteristic. In fact, this particular characteristic was the most frequently noted among all of the four themes with ten of the fourteen study participants citing its association with their admired leader. One study participant summarized this characteristic in the following way,

I would start of with Jesus of Nazareth. I've read Gandhi and Martin Luther King and people involved in the non-violence [movement]; leaders who clearly loved mankind - all were willing to pay any price they had to pay in order to accomplish what they needed. I was in high school when Kennedy was assassinated, and then a few years later, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King. I watched a lot of these people who were extraordinary leaders sacrificed. [They] believed so much in what they were trying to accomplish for the good of others, and so personal sacrifice is often the consequence of it. (SP5)

"Other"-interest was the third most frequently identified characteristic theme associated

with the named admired leaders of the study participants. As noted in Table 26, "other"-interest falls just behind that of determined resolve. The most frequently mentioned characteristic representative of this theme was "commitment to the service of others". One study participant expressed his thoughts this way,

I know a lot of people who I think are good examples, exceptional leaders; those who are effective in serving and inspiring the people they work with. Like a hospital I know in Haiti - there's a physician who was a colonel in the US Air Force and 20 years ago he resigns his commission, goes to Haiti and starts a hospital on a dirt road with no electricity - nothing! He was Board certified as a Fellow in the American College of Surgeons. That guy is extremely inspirational in the sense that his whole life is in service to others. He is foregoing a very comfortable life to do that. (SP9)

Commenting further on the theme of "other"-interest, the transformative actions of Rosa Parks refusing to relinquish her seat on a public bus during the civil rights movement of the 1960s was recalled by one respondent,

An individual who comes to mind is Rosa Parks. She wasn't flamboyant, [her actions were] a result of her personal convictions and a personal sense of who she was and knowing that in order to serve others, there would be a price to pay. [She had] that inner sense of commitment and confidence and self-assurance that it was the right thing to do. Then you look at where [her actions] have gone and the results of that very simple act. She didn't do it for notoriety, but rather for personal conviction and to ultimately serve others. (SP10)

Finally, of interest was the response offered by study participant 3. In contrast to the 13

other participating leaders, she did not identify a single admired leader, but described a fictitious leader as an amalgam of many individuals.

I don't have one individual... to me an exceptional leader is an amalgamation of [various] characteristics that I have tried to dissect and have tapped from a large number of people with whom I have worked. I think one of the most important skill sets I've tried to adopt is collaboration - how you turn high-level people into a collaborative group working toward common goals or at least not impeding each other. So, I don't have one person, but pieces of a whole group of people who I have looked to learn from. (SP3)

By asking each study participant leader to identify a leader(s) they personally admired,

along with the characteristics which exemplify their lives, this study attempts to peer into the minds of the study participants in order to deductively discern those leadership characteristics, which may inform their lives. Twenty-five (25) unique characteristic descriptors were noted from which the three significant themes, previously associated with the study participant responses concerning essential traits and behaviors emerged: emotional intelligence, determined resolve, and "other"-interest.

An amalgam of elements in useful toward addressing research question 1 (R1), that is,

"What are the key characteristics of healthcare professionals who are perceived to be transcendent leaders?" Thus far, this study has investigated the personal and organizational contexts of the study participants, their core personal values, perceptions of essential traits and behaviors, spiritual proclivity, motivating techniques, life experiences which may inform their leadership actions, and inquiry into characteristics associated with admired leaders. A self-reflective examination of study participant leadership style further enriches this examination and contributes to the purpose of this study.

Category of Data #10: Self-Reflection Concerning Leadership Style

In considering a context in which to frame the study participant responses to their self-

perceived leadership styles, several models were considered (Bass, 1985; Goleman, et al., 2002; Hay/McBer Consulting Group, 2000; Lipman-Blumen, 1956). Goleman, et al (2002), drawing upon the earlier work of the Hay/McBer Consulting Group (2000), provides a construct which conjoins contemporary research in leadership behaviors with the conceptions associated with emotional intelligence. Stipulating Goleman's et al. (2002) leadership style framework was therefore considered reasonable in analyzing the self-reflective responses of the study participants. In advance of presenting the findings associated with this category of data, one caveat is worth of note. In each of the study participant's interviews, there was a working assumption between the researcher and respondent that the style of leadership employed by the leader is mutable. That is, leadership behaviors change given the situation, knowledge of follower(s), culture of the organization, and a host of other factors. Exceptional leaders, including the participants in this study, would broadly affirm that "leaders with the best results do not rely upon only one leadership style; they use most of them depending on the situation" (Goleman, 2000, p. 80). Therefore, study participant responses herein reported might best be considered their default, or general manner, in relating to their followers.

When asked, "How would you describe your leadership style?", 53 descriptive phrases or

terms were used ranging from the democratic, "My style is one of involvement - bringing people together" (SP4), to the directive, "I'm focuses, pragmatic, and expect others around me to be equally competent. My [leadership] style involves deeply held principles" (SP5). After interpreting the individual comments offered by each study participant, Goleman's et al. (2002) leadership style framework provided a useful mechanism for each respondent to be assigned to the style that most closely reflected their comments. Table 27 provides a summary of six leadership styles, as well as the assignment given to each participating leader in this study.

Table 27

Self-reflected leadership style of study participants.

Source: Adapted from D. Goleman, R. Boyatzis, and A. McKee. Primal Leadership, 2002.

Of the 14 study participants, three (n=3) were considered to exhibit a visionary

leadership style, four (n=4) evidenced an affliliative leadership style, four (n=4) are considered to have a democratic leadership style, two (n=2) reflected a coaching style of leadership, and one (n=1) suggested a pacesetting style. No participant evidenced a commanding (coercive) style of leadership. Of the 14 respondents, thirteen (n=13) evidenced leadership style behavior which, according to the Goleman, et al. model, would have either a "positive" or "most highly positive" overall impact on the work environment. One (n=1) study participant expressed leadership behaviors which would suggest a negative overall work environment impact if this style were not regularly altered or modified to reflect the situation, follower needs and expectations, or other contextual factors.

Affiliative or democratic styles of leadership were the most frequently evidenced among t

the study participants. One respondent defined his affiliative style as,

I try first to lead by the example I set - by being honest, by being truthful with people, and by being loyal and supportive to people. I try to bring people into the dialogue about vision and goals, which will best serve the organization - our patients - our colleagues and each other. Ultimately [my style of leadership] is to be a leader who serves others and in doing so they get charged up about wanting to do more themselves. Service to others is really quite an eloquent style of leadership in the more you - as the leader - give, the more comes back to you from those you lead. (SP1)

A democratic style of leadership implies a leader's desire to involve followers in

decision-making through active participation. This earnest intent to involve followers was noted by study participant 11.

I believe folks would say that my style is one of engagement - bring others into solving problems. And respect - respecting the talents of others. I would like to believe that my style represents an honest, hardworking, and passionate style that values and empowers others. (SP11)

A visionary leadership style was felt to best reflect three of the study participants. One

noted, "I guess I would say that my style of leadership involves inspiring others to live up to their potential so that we can achieve our social and community ambitions" (SP6). Another offered a more prolific response,

I suppose you could describe my style as supportively involved. I set vision and the general culture and then let the people develop their own groundswell of enthusiasm. Movements - be they peace movements, or anti-apartheid movements, or whatever, are born because of some person with a dream - with a vision of a better future - and stands up against might big odds and sets into motion the desire of many. In a small way, that's how I describe my style of leadership - I try to understand the desires of people, I articulate that dream, and set into motion [their] collective energies. (SP12)

A fourth style of leadership evidenced by two (n=2) of the study participants is termed

the coaching style. This involves leadership behavior intended to connect followers to the long-term aspirations of the organization. Study participant 7 expressed this as follows:

I suspect that I have a variety of styles depending on the people I'm dealing with and the sitaution, but if I had to say just one style, I guess it would be that I try to inspire people to look at the bigger and broader scheme of things and how we can together meet the interests of others before our own interests. (SP7)

Finally, one study participant was notably strident in describing his pacesetting style of

leadership; an obvious discrepant theme within this category of data. He stated,

My style evolves from principles that are deeply held and intrinsic. And they are not situational; my leadership has a clear sense of purpose. And I think that it's [my style] simultaneously inclusive of others and exclusive in that it probably drives the culture [around me] to align or repel - attract or repel. You just have to accept that as part of [my] leadership. I'm focused, pragmatic, and I expect that those around me are equally competent at what they do. (SP5)

In summary, the self-perceived styles of leadership attributed to the study participants

were juxtaposed to Goleman's et al. (2002) leadership style model as a means of framing the analysis. Of the six styles within the model, study participants were assigned to five including the visionary style, affiliative style, democratic style, coaching style, and pacesetting style. In terms of the impact on the overall climate of their organizations, the participating leaders self-described behaviors might be considered "positively" or "most strongly positive". Only one of the study participants self-identified a leadership style which might be considered to have a negative overall impact on the climate of an organization.

If a theme can be drawn from this category of inquiry, it is that the study participants

perceived their style of leadership as one that engages their followers in an effort to establish emotional bonds as a prerequisite to pursuing socially beneficial causes.

A final comment by one participating leader suggests an association between a leader's

style and a moral imperative. He commented,

I would suggest that the best leaders live their lives in the pursuit of moral purposes; how to help humanity, how to help my neighbor, and how to bring different peoples together to reach agreement. I think what makes them great leaders is their desire and courage to help others even if they're at risk of harm or ridicule. (SP2)

An inquiry into the moral imperative of leadership, as perceived by the study participants, contributes to the expanding understanding of the leadership dynamic as experienced in the lives of perceived transcendent leaders.

Category of Data #11: Perceptions Concerning a Moral Imperative

Ascribing with certainty a moral imperative to the leadership phenomenon is polemic.

That is, what universal standards define moral or ethical virtues relative to the act of leading others and how do these virtues manifest themselves in the leader-follower dyadic relationships? Steidlmeier (1995), for example, has suggested that love, work, fairness in exchange, ownership, and friendship are universal moral values found in broadly diverse cultures around the world; "regardless of the social customs and practices through which they are realized" (In Bass & Bteidlmeier, 1998, p. 6). Moreover, if legitimate leadership does in fact imply an ethical or moral dimension, does the requirement invoke a mandate to pursue goals that have broad social purposes? Gini (1996) offers a relative response to the former question by asserting,

... all leadership, whether good or bad, is moral leadership at the descriptive if not the normative level. To put it more accurately, all leadership is ideologically drive or motivated by a certain philosophical perspective, which upon analysis and judgement may or may not prove to be morally acceptable in the colloquial sense. (p. 10)

Adding to this ambiguity, Dewey (1960) attempted to frame mortality within the context of a culturally defined and embraced set of rules or standards that are external to the individual, yet habitual. He suggested that morality is comprised of two aspects: the standards (moral guidelines) which society adopts and reflective conduct, or personal actions that define ethics.

Moral leadership has been viewed through the litmus of a leader's personal character.

In Nichomaclean Ethics, Aristotle (1998) argued that character was the most illusive aspect of leadership and posted that a moral leader should possess the virtues of courage, temperance, generosity, self-control, honesty, sociability, modesty, fairness, and justice (Velasquez, 1992). Sheehy (1990) would add that the "issues of leadership are of today and will change in time. Character is what was yesterday and will be tomorrow" (p. 311). More recently, Anello and Hernandez (1996) would ascribe to moral leadership six essential elements: service-oriented leadership, personal and social transformation as the purpose of leadership, the moral responsibility of investigating and applying truth, belief in the essential nobility of human nature, transcendence (e.g. overcoming ego and selfishness), and the development of capabilities (p. 61).

Given the variety of perspectives in attempting to associate a moral imperative to the

leadership phenomenon, it is reasonably stipulated that the genesis of ethical leadership conduct is rooted in the moral standards held by the leader and, in turn, "the [moral] values promoted by the leader have a significant impact on the values exhibited by the organization [and its followers]" (Northouse, 2001, p. 255).

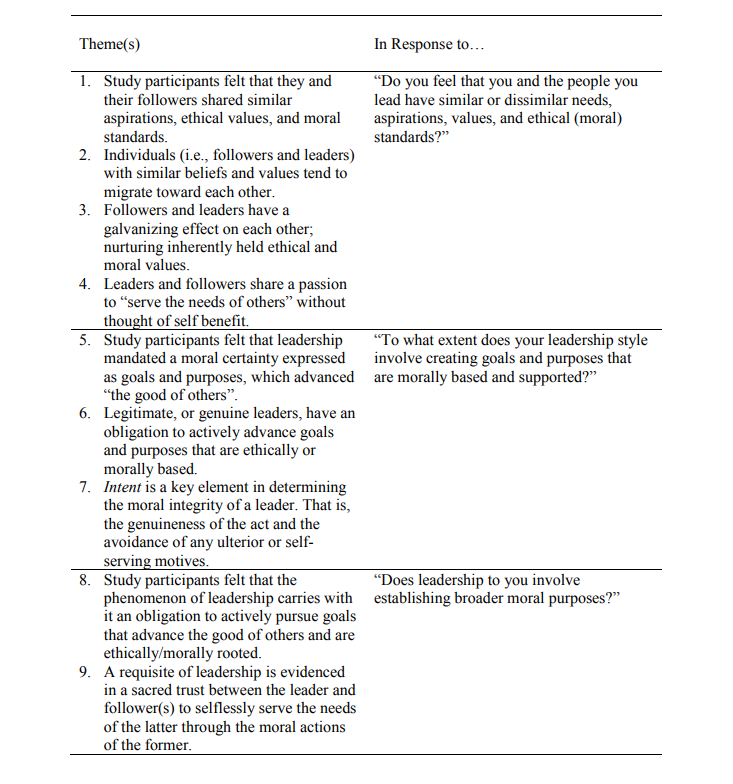

Understanding the study participant perceptions concerning the distinguishing aspects of

moral standard and ethical conduct serve to offer a unique insight into the leadership experience as evidenced in the lives of perceived transcendent leaders. Three questions posed to the study participants comprise this category of data. The first question asked, "Do you feel that you and the people you lead have similar or dissimilar needs, aspirations, values, and ethical (moral) standards?", elicited broadly similar responses. Each of the fourteen study participants affirmed that both they and the people they lead - and for that matter, associate with outside of the work environment - have similar aspirations, as well as moral standards. This may suggest that the moral values shared by leaders and those led have a synergistic relationship, each having the capacity to support or moderate the other. Wills (1994) notes that [moral] leadership is a mutually determined activity on the part of the leader and those led (p. 13). This notion of mutuality is alluded to by one study participant as,

Ethical standards are grass root ideals and you know early on if you're in sync with someone or not. If not, you tend to move away from their sphere of influence instinctively. So I believe my moral and ethical beliefs about care and service have influenced those I work with and certainly their needs and values have influenced my own. (SP8)

Migrating toward people and organizations in which followers and leaders feel a sharing of basic beliefs and aspirations was a significant theme noted by the respondents. Study participant 7 stated,

I think human nature dictates - to some extent- that we gravitate to those people and situations that we feel most comfortable with or relate to, and so, I would say that folks I work with and lead have fairly close needs and aspirations and ethical standard... we all want to help others feel better physically, emotionally, and spiritually. (SP7)

Study participant 11 expressed a similar sentiment noting, "Organizational culture, in my opinion, is a lot like a vacuum which draws into it people whose interests and values are familiar". Another responding leader perhaps best summarized the sentiments expressed by the study participants in commenting,

I think people tend to gravitate to clubs, friends, churches, and workplaces that hold values that are closely aligned with their own. If they're not similar, then I believe they tend to move along. That's where the role of the leader becomes evident, they set the tone for the organization, or school, or team, or whatever group. People of like minds tend to gravitate to them. So, I would say that folks that I lead have similar aspirations and moral standards to me - and I to them. We all want to do the right thing for others, we all want to make a difference, and we all want to feel we've contributed to a greater good - a societal good. (SP14)

Acting selflessly for the benefit of others was an additional theme noted by the study

respondents in answer to the question, "Do you feel that you and the people you lead have similar or dissimilar needs, aspirations, values, and moral standards?" Study participant 9 stated, "The desire to help has got to be a driving influence that we all share - it's even more than a desire, it's a passionate need to want to reach out and do something good for someone else." Another respondent noted, "People in healthcare come to the profession because they have a desire to serve the needs of others" (SP10). And finally, one leader offered,

Certainly there are difference which exist, but if you mean by "moral standards" the sacred appreciation of life - not matter how humble the person may be; the understanding that we do not harm to a person; and that our first and highest calling in life is to concern ourselves with our family and others before ourselves - then, on balance, I believe that most everyone I work with or associate with share these moral standards. (SP1)

Demonstrating complete accord, the study participants expressed a belief that the needs,

aspirations, and moral values they held dear were compatible to those held by those thy led. The respondents felt that leaders and followers had a mutual effect upon one another; galvanizing and nurturing inherently held ethical and moral values and that this synergy was expressed in the attraction of followers to leaders and, in turn, leaders to organizations which evidenced similar beliefs and ambitions. An additional theme that emerged in the comments noted by the study participants was the expressed desire to do something of benefit for others or for broader social causes. That is, the respondent leader felt that their colleagues and followers shared the same passion they held most dear; to serve the needs of others.

A second question considered part of this category of data, and intended to further

explore the relationship between moral virtue and leadership as experienced by the study participants was, "To what extent does your leadership style involve creating goals and purposes that are morally based and supported?". Study participants, once again, fully concurred in asserting that the privilege of leadership mandated a moral certainty as expressed in goals and purposes which advanced "the good of others". This significant theme of service to others permeated the study participant responses. Study participant 3 noted, "Exceptional leaders advance morality through their actions, their honesty, and their commitment to an ideal of service [to others]." Another expressed this same sentiment in a more passionate 'voice',

I believe that if you're in a position of leadership, you are obligated to set the highest ethical and moral standards. As such, the act of leadership - regardless of style - by its nature should involve the establishment of higher purposes; to help others to genuinely care about human beings, to show our own humanity and vulnerability. (SP4)

Inferring there exists an obligation on the part of a leader to advance goals and purposes

that are morally based, study participant 2 noted, "... the best leaders live their lives in pursuit of moral purposes; how to help humanity, how to help your neighbor, how to bring different people together...". Echoing this opinion, study participant 6 commented,

Yes, absolutely. If what I do and how I lead is not based on furthering a moral and higher purpose, then I'm not acting as a leader. Genuine leaders, in my opinion, always hold up their own actions to a moral compass that guides them in their daily efforts.

Another respondent queried, "Isn't that a core element of leadership - to establish purposes which have some moral and practical good for the benefit of another...?" (SP11). The opinion offered by study participant 10 could very well serve as a response to this rhetorical question,