"Expanding the transactional-transformative paradigm"

Leadership Research by

Dr. David A. Jordan

President, Seven Hills Foundation

Chapter Two

Disagreement about the definition of leadership stems from the fact that it involves a complex interaction among the leader, the followers, and the situation. Some researchers define leadership in terms of personality traits, while others believe leadership is represented by a set of prescribed behaviors. In contrast, other researchers believe that the concept of leadership doesn't really exist.

Robert Kreitner and Angelo Kinicki (1998)

Review of the Literature

Introduction

The purpose of this literature review is to synthesize and analyze the published literature

concerning an emergent leadership construct variably termed transcendent, transcendental, or transcending leadership. Researchers investigating the phenomenon suggest that transcending leadership is an iterative extension to the extant transactional-transformational leadership paradigm. While there exists an abundance of published materials on transformational leadership - including more than 650 dissertations in various disciplines that have the term "transformational leadership" in the title (University Microfilm International, 2004) - therre is by comparison a meager sampling of published literature on the nascent transcending leadership phenomenon. This study seeks to discern the reasonableness of a transcending leadership construct by filling the gap in knowledge between those characteristics of transformational and trasactional leadership, which have been established in the literature and the unique aspects of transcending leadership, which remain undetermined.

Overview of the Review of the Literature

The review of the literature for this study incorporates two areas of focus. The first area

of focus involves a cursory review of extant literature by Burns (1978) and Bass and Avolio (1994) concerning the transactional-transformational leadership paradigm. The second area of focus considers propositions asserted to by Larkin, 1994; Aldon, 1998; Cardona, 2000; and Crossan, Nanjad, and Vera, 2002, who posit divergent bases for a transcending leadership phenomenon. A review of the bases upon which each of the four propositions is established is presented as contextual background in advance of a descriptive analysis of the respective studies.

In his seminal text, Leadership, Burns (1978) conceptualizes the constructs of

transactional and transformational leadership. This leadership paradigm has permeated leadership theory and research since its publication and is considered the fount from which new leadership (Bryman, 1993), theories, constructs, and approaches have emerged. Bass and Avolio (1994), in Improving Organizational Effectiveness through Transformational Leadership , broadens and enriches Burns' (1978) model with the introduction of their full range of leadership model. If it can be said that Burns is the conceptual architect of transactional-transformational leadership theory, then it must be stipulated that Bass and Avolio (1994) are the preeminent journeymen in operationalizing the paradigm. Drawing an inference from Burns' (1978) work, several researchers have recently begun exploring transcending leadership as a discrete construct, which could serve to extend the full range of leadership model. Though briefly mentioned by Burns, neither he, nor Bass and Avolio (1994) delve into the prospective phenomenon of transcending leadership to any meaningful extent.

A further area of focus in the review of the literature is to examine the parsimonious

research conducted on a transcending leadership construct. In her doctoral dissertation, Beyond Self to Compassionate Healther: Transcendent Leadership, Larkin (1994) suggests that transcendent leadership embodies a spiritual dimension, rooted in the dynamic of spiritual leadership. In a second study, Aldon (1998) ascribes a metaphysical perspective to the transcending leadership phenomenon in her thesis entitled, Transcendent Leadership and the Evolution of Consciousness. Aldon suggests that transcendent leadership is a consequence of the natural evolution of human consciousness. A third analysis by Cardona (2000), Transcendental Leadership, posits that the construct is fundamentally an enhanced exchange relationship between leaders and led where a willful desire to be of service to others is a defining characteristic. Finally, the work of Crossan, Nanjad, and Vera (2002), Leadership on the Edge: Old Wine in New Bottles?, suggests that the transcendent leadership phenomenon is a function of strategic leadership anchored in organizational learning.

Each of the nascent works on transcending leadership offers a disparate view on the

essence, or rich meaning, of a prospective leadership construct built upon the foundation of normative transactional-transformational leadership theory. While each suggests the presence of a transcending leadership phenomenon, none have conducted a comparative analysis of their respective assertions with the goal of conflating their disparate viewpoints. Rather, each study focuses on a particular point of view - or structural basis - and seeks to justify its perspective from that vantage point. By drawing inferences from each of the identified sources and comparing these inferences to characteristics evidenced in the lives of perceived transcendent leaders and normative transactional-transformational leadership theory, it is possible to gain insight into a body of knowledge relevant to this study.

The Evolution of Leadership Theory and Emergence of the Transactional-Transforming Paradigm

Beginning a meaningful inquiry into the reasonableness of a transcending leadership

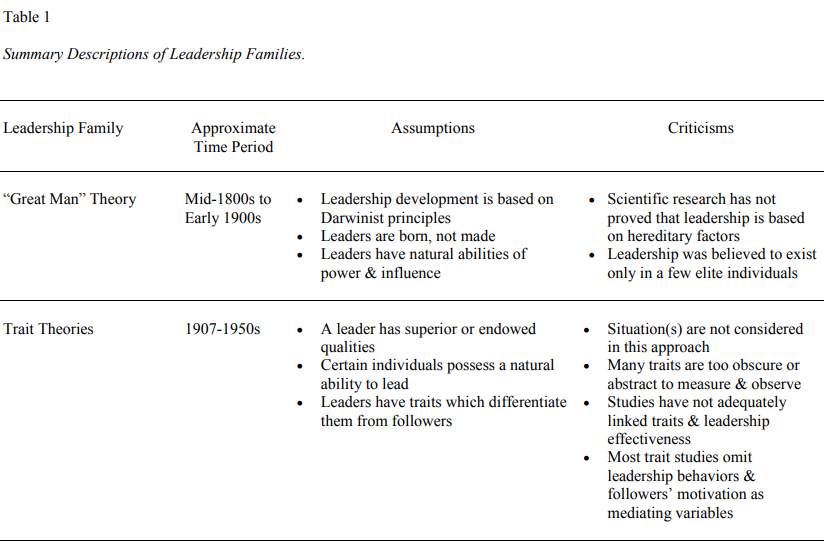

construct demands an examination of the theoretical development of extant leadership theory with particular emphasis given to the transactional-transformational paradigm. Thoughtful academic research on the phenomena of leadership is generally agreed to have emerged toward the end of the 19th Century and early 20th Century (Chemers, 1997; Northouse, 2001; and Stogdill, 1974). Over the past 150 years, five families of leadership theory have emerged, as depicted in Table 1 (Summary Descriptions of Leadership Families). During the initial era of inquiry, Darwinist thinking prevailed, and leadership was thought to be based on heriditary properties (Bass, 1981). Such great man theory approached sequeiaed into an attempt to understand leadership by assessing leader traits. Trait theories, which surfaced in the early part of the 20th Century, prevailed for nearly five decades as preeminent leadership constructs, stipulating that leaders possessed certain characteristics, such as height, intelligence, and self-confidence, which set them apart from followers (Appendix A: Selected Leadership Trait Studies). By the 1950's, however, the field of psychology began to influence the frameworks in which researchers viewed leadership. Behaviorists suggested that leadership could more accurately be understood in behavioral terms, promoting the notion that establishing meaningful relationships with followers and creating task accomplishment structures were critical aspects from which to understand the nature of leadership (Appendix B: Selected Leadership Behavioral Studies). These behavior theories did not, however, adequately address situational variables and group processes (Yukl, 1994). A response to this shortcoming came in the advancement of situational-contingency theories in the 1960s, which proffered that leaders should adapt their approaches or actions pursuant to the context or situation. That is, accoridng to situational-contingency scholars, the situation dictates who emerges the leader or "the product of the situation" (Bass, 1990, p. 285). Situational-contingency theories, like trait and behavior theories, are primarily leader oriented where followers are considered the beneficiaries of leader influence.

Table 1

Summary Descriptions of Leadership Families.

Source: Adapted from S. R. Komives, N. Lucas, & T. R. McMahon, Exploring Leadership for College Students Who Want to Make a Difference, (1998).

Dissatisfied with the situational-contingency theories' lack of attention to mutuality

between leaders and followers, researchers have begun to describe the nature of leader-follower relationships as reciprocal exchanges where activities result in a synchronicity of goal and need achievement. This thread of leadership research recognized that individual, group, and organizational performance is manifested in the mosaic of the social interplay between leaders and followers (Chemers, 1984). Recently introduced theories (House & Aditya, 1997) of leadership have attempted to integrate the interpersonal and intra personal dynamics found among individuals, groups, organizations, and societies. Appendix C (Leadership Theory Taxonomy) suggests a taxonomy of the leadership families and the respective theories, constructs, and approaches associated with each. It is instructive to note the iterative progression of leadership constructs over the chronological timeline and the migration of bases upon which the constructs have emerged. This suggests that leadership theory is in a perpetual process of refinement.

Among the integrative "new leadership" (Bryman, 1993) approaches to leadership theory,

one particular paradigm has received notable attention in the literature - the full range of leadership model. Inspired by Burns (1978) and operationalized by Bass and Avolio (1994), the full range of leadership model integrates the two constructs of transformational leadership and transactional leadership by delineating seven behavioral factors, and adding a laissez-faire (nontransactional) leadership dimension. As a means of accounting for the differences between revolutionary, rebel, reform, and ordinary leaders, Downton (1973) was first to suggest distinctions between the normative transactional leadership construct and a then new proffered transformational construct (Bass, 1990, p. 223). Later, Burns (1978) conceptualized a transactional-transforming leadership paradigm, which in turn was expanded upon and operationalized by Bass (1985) and Bass and Avolio (1994) as the full range of leadership model. The study of transformational leadership and its related transactional construct have since permeated the new leadership literature. In his seminal work on leadership, Burns (1978) presents his notion of transactional and transforming leadership within the context of political and social change milieus. He contends that,

The essence of leader-follower relation is in the interaction of persons with different levels of motivation and power potential in the pursuit of a common or at least joint purpose. That interaction, however, takes two fundamentally different forms [transactional and transforming] (p. 18)

As seen by Burns, transactional leadership is merely an economic exchange relationship (Blau, 1964; Homans, 1961); a formal transaction of goods for money, current influence for future favors, or other quid pro quo transactions. In the transactional construct, a leadership act takes place, but not one that ties leader and follower together in the mutual pursuit of a higher ideal. Burns (1978) further clarifies this definition by explaining that transforming leadership "occurs when one or more persons engage with others in such a way that leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality" (p. 20). For leadership to be transforming, Burns designates three tasks. First, it positively affects the exchange relationship (mutuality) between leaders and followers. Second, an enhanced organizational culture is created by transforming leadership, inspiring followers to become more highly motivated. Third, transforming leadership stimulates positive social change both within the organization and external to it (Couto, 1993). Burns (1978) refers to this final task as moral leadership, stating " ... the kind of leadership that can produce social change that will satisfy followers' authentic needs" (p. 4). Not satisfied with having addressed the term once, Burns offers a further clarification when he suggests that moral leadership - also referred to as ethical leadership - "emerges from, and always returns to, the fundamental wants and needs, aspirations, and values of the followers" (p. 4). Figure 1 suggests a conceptualization of Burns transactional-transforming model as a hierarchical continuum.

Figure 1. Conceptualization of Burns' (1978) Transactional-Transforming Model of Leadership with behavioral descriptors. Arrows suggest a flow of leadership practice within a hierarchical continuum.

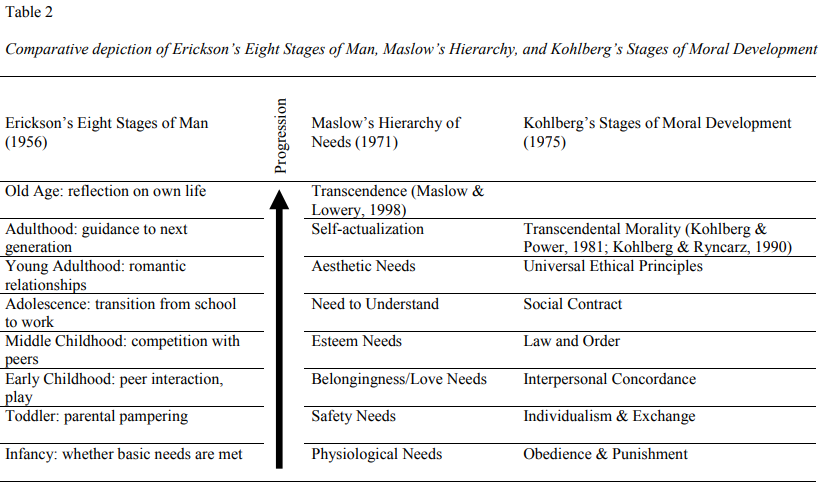

Burns (1978) drew upon Maslow's (1971) hierarchy of needs model, Kohlberg's

(1975) stages of moral development, Rokeach's (1973) structure of human values and Erickson's (1956) theory of psychosocial development as contextual factors to conceptualize his transactional-transforming leadership paradigm and the exigency of moral leadership. Burns felt that the congruence between human need, values, and moral development hierarchies contributed to the manifestation of "purposeful leadership" Burns, 1978, p. 44).

A congruence between the need and value hierarchies would produce a powerful potential for the exercise of purposeful leadership. When these hierarchies are combined with stage theories - for example, Erickson's eight psychosocial stages of man ... leadership, with its capacity to exploit tension and conflict finds an even more durable foundation (p. 44)

Burns posited that these hierarchies have a mutual influence on each other. That is, the conflicts a leader experiences during his or her stages of life (Erickson, 1956) can be resolved either positively (adaptive) or negatively (mal-adaptive) and that these "crisis points" impact the leader's moral development and values - either migrating the leader successfully upward through the hierarchical continuums or at a level of stasis. Bass and Avolio's (1994) full range of leadership model complies with Burns (1978) view that a principle function of leaders is in assisting followers to move upward through hierarchical levels of human needs, stages of moral development, and a structure of human values (p. 428). Table 2 provides a comparative depiction of the theories stipulated by Erickson (1956), Maslow (1971), and Kohlberg (1975). It is noteworthy that Maslow and Lowery (1998) added an additional "transcendence" level to Maslow's (1971) original hierarchy well after the publication of Burns (1985) seminal work. Maslow and Lowery (1998) suggested that while the self-actualization level involved finding self-fulfillment and the realization of one's own potential, the higher transcendence level concerns itself with helping others find self-fulfillment and the realization of their potential. Similarly, Kohlberg and Power (1981) and Kohlberg and Ryncarz (1990) broadened Kohlberg's (1975) six stages of moral development and positied the feasibility of a seventh stage - transcendental morality - which would affiliate non-dogmatic spiritual beliefs, or "transcendental properties", with moral reasoning (Sonnert & Commons, 1994).

Table 2

Comparative depiction of Erickson's Eight Stages of Man, Maslow's Hierarchy, and Kohlberg's Stages of Moral Development

Finally, Burns (1978) suggests a new, and perhaps, richer dimension to his transactional-

transforming leadership paradigm. He suggests the notion of a transcending leadership dynamic and posits the following description:

Transcending leadership is a dynamic leadership, in the sense that the leaders throw themselves into a relationship with followers who will feel elevated by it and often become more active themselves, thereby creating new cadres of leaders. Transcending leadership is leadership engagé. (p. 20)

While Burns suggests the idea of a transcending leadership, he does not fully incorporate it into his model of leadership theory. Instead, he offers it as an architect would a spandrel - an artifact that is left over in the execution of an original design - leaving the reader to interpret its significance. Figure 2 theories an expansion to Burns' transactional-transforming leadership model with the addition of a transcending leadership construct.

Figure 2. Conceptualization of a Burns (1978) inspired Transactional-Transforming Model of Leadership with the addition of a proffered transcending leadership construct. Arrows suggest a flow of leadership practice within a hierarchical continuum.

Subsequent to Burns (1978), a further elaboration on the transforming and transactional

leadership constructs was initiated by Bass (1985), culminating in the research by Bass and Avolio (1994). A fundamental departure between Burns (1978) and the early work of Bass (1985) concerned the relevance of a moral foundation as an integral aspect of transformational leadership. Bass posited that "transformational leaders vary from the highly idealistic to those without ideals" (Bass, 1985, p. 185) thus associating the malevolence of Hitler with the benevolence displayed by Gandhi. Bass discarded the attributes of moral good or evil and simply envisioned transformational leadership as producing change (Carey, 1992, p. 220). Bass & Avolio (1994) would later redress this discord and ascribe a moral imperative to transformational leadership. Bass & Steidlmeir (1999) would further pursue the relevance of a moral foundation and assert that authentic transformational leadership, as opposed to pseudo-transformational leadership, must incorporate a central core of moral values (p. 210).

[Authentic transformational leadership integrates] the moral character of the leaders and their concerns for self and others; the ethical values embedded in the leader's vision, articulation, and program, which followers can embrace or reject; and the morality of the processes of social ethical choices and actions in which the leaders and followers engage and collectively pursue. (p. 181)

The premise behind Bass and Avolio's (1994) full range of leadership model is that leaders demonstrate a range of transactional and transformational styles that may be categorized within a matrix of dimensions - effective vs. ineffective and passive vs. active. Within the model, leaders display gradations of competency in matching the frequency of each style they employ to the situational demands which concurrently understanding the psychological variables associated with the situation (i.e., how one motivates followers through positive exchange relationships, etc.) Bass and Avolio posit several factors, or behavioral descriptions of leadership action, within the full range model. The assert that laissez-faire leadership "is the avoidance or absence leadership, and is, by definition, the most inactive - as well as the most ineffective" (p. 4). Moving up the continuum are three additional transactional leadership styles: positive management by exception (MBE-P), active management by exception (MBE-A), and contingent reward (CR). The leadership style which Bass and Avolio proffer to be most active and effective - transformational - is positioned at the top of the model's continuum. Transformational leadership embodies four leadership behaviors (factors) - idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Idealized influence - the first of four transformational leadership factors - involves leader behavior which engenders follower admiration, respect, and trust. Behavior associated with idealized influence includes: considering the needs of others in advance of personal needs; consistency in action; demonstrating high standards of performance and moral conduct; and avoiding the use of power for personal gain (Avolio & Bass, p. 2). Inspirational motivation is associated with follower motivation and inspiration stimulated by leader behavior. Enthusiasm, team spirit, open communication and shared vision are hallmark characteristic of inspirational motivation (p. 2). The third transformational leadership factor, intellectual stimulation, is indicative of leadership behavior which encourages follower creativity, innovation, and the challenging of the status quo. Individualized consideration is the final factor associated with transformational leadership and involves "special attention to each individual's [followers and colleagues] needs for achievement and growth by acting as a coach or mentor. Followers and colleagues are developed to successively higher levels of potential" (p. 3)

Bass and Avolio (1985) ascribe certain factors to the transactional construct. They

include: contingent reward, management by exception (active and passive), and the previously noted laissez-faire dimension. Contingent reward involves leader-follower agreement on assignments or tasks to be performed along with the compensation (reward) to be given assuming a satisfactory completion of the task. Management by exception involves a "corrective transaction" (Avolio & Bass, 2002, p. 4), which is evidenced either actively (i.e., the leader proactively monitors the performance of the follower(s) and takes immediate action to correct any deviances or errors from established standards) or passively (i.e., the leader waits for mistakes or deviances from established standards to occur; notes them; and then instigates corrective action.) Figure 3 depicts the full range of leadership model as presented by Bass and Avolio (1994).

Figure 3. Bass and Avolio's (1994) Full Range of Leadership Model with behavioral factors. Key: 4 I's (Idealized Influence, Inspirational Motivational, Intellectual Stimulation, Individualized Consideration); CR (Contingent Reward); MBE-A (Management by Exception - Active); MBE-P (Management by Exception - Passive); LF (laissez-faire) leadership.

Source: Adapted from B. M. Bass and B. J. Avolio, Improving Organizational Effectiveness through Transformational Leadership, 1994.

Bass (1985), perceiving transactional and transformational leadership as complementary

constructs, developed the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) as a means of assessing transactional and transformational leadership behavior and the relationship between leader behavior and style with organizational effectiveness and follower satisfaction. Based upon the factors associated with the full range of leadership model (Figure 3), several iterations of the MLQ have been developed and made subject to extensive critical review (Antonakis, 2001; Lowe & Kroech, 1996) conforming its dominance as the preeminent model within "new leadership" (Bryman, 1993) theory. Avolio and Bass (1991) subsequently developed a Full Range of Leadership Development Program, which involves the MLQ assessment, feedback, and leadership coaching.

It is noteworthy that Burns (1978), with few exceptions, uses the term "transforming"

leadership while Bass (1985) and Bass and Avolio (1994) modified the descriptor to "transformational" leadership. Couto (1993) suggests that this distinction reflects a fundamental discord in the context from which Burns (1978) and Bass and Avolio (1994) approach their respective leadership constructs. Couto (1993) posits that Bass and Avolio's (1994) use of the adjective form of a noun, "transformation", modifies leadership and suggests a condition or state, whereas Burns' use of the term "transforming" implies the adjective form of a verb, which conceptualizes leadership as a process (In Wren, 1995, p. 104). This distinction has a bearing on the directionality of influence between leaders and followers. A transformational process infers that the leader is imbued with with the influential power to transform followers - a unidirectional dynamic. In constrast, the transforming process suggested by Burns (1978) asserts a bi-directional influence where leaders and followers may, through their mutual interactions, transform one another.

While Bass and Avolio (1994) provide to the dyadic transactional-transformational

structure the useful addition of a laissez-faire leadership dimension, along with other behavioral factors, they did not meaningfully address the nascent transcending leadership construct suggested by Burns (1978). Only recently has this phenomenon garnered attention from scholars. Burns' mention of a transcending leadership dimension that potentially broadens the extant transactional-transformational paradigm has stimulated an inchoate inquiry into the plausibility of a transcending leadership construct.

Thus far, a review of the literature has explored the prevailing transactional-

transformational leadership paradigm within the historic context of leadership theory. A cursory background on the paradigm is offered in order to establish a future juxtaposition with a nascent leadership construct - transcending leadership - which serves as the focus of this study. Table 3 (Comparison of characteristics associated with extant transactional-transforming leadership theory) provides a summation of the contextual background on the transactional-transformational leadership paradigm. What follows thereafter is an examination of the propositions put forth in the literature concerning a transcending leadership construct, along with a review of the contextual bases of each.

Table 3

Comparison of characteristics associated with extant transactional-transforming leadership theory as stipulated by Burns (1978) and Bass and Avolio (1994).

Transcending Leadership as a Spiritually Oriented Construct?

Background

Researchers and scholars have recently begun investigating the prospective relationship

between the dynamics of leadership and a leader's spiritual identity. Marinoble (1990), attempting to develop a clearer understanding of the ways in which the development of personal faith interacts with the process of transformational leadership, determined that spiritual faith had a diversity of meanings among the 12 study participant leaders interviewed in her study, and that "[spiritual] faith was viewed as a foundation to their leadership by some, but not all, participants" (p. i). In a Delphi study involving 22 national leaders, Jacobsen (1994) concluded "a strong inference that spirituality and transformational leadership are related" (p. 30). Jacobsen further concluded that leaders and followers seek more than extrinsic (economic) rewards in the workplace. Instead, they are redefining the nature of work to include aspects of spiritual identity and spiritual satisfaction. Fifty-nine percent (59%) of Jacobsen's study participants felt a greater integration of spirituality in the workplace was needed (p. 83). Beazley, H. (1997) extended the study of spirituality in organizational settings by proposing to construct a definition of spirituality an an associated leader spirituality assessment scale. Using a sample of 332 participants to define both the "definitive and correlated dimensions of spirituality" (p. 104), the study determined three correlated dimensions - service to others, humility, and honesty - and one definitive definition of spirituality - "living in a faith relationship with the Transcendent that includes prayer or meditation" (p. 173). A follow-up study by Beazley, D. A. (2002) was conducted for the purpose of investigating the premise that servant leaders are tacitly spiritual and that their spirituality correlates with the performance of managers in carrying out their leadership activities (p. 7). This study confirmed the correlated dimensions of spirituality - humility, honesty, and service to others - among organizational managers perceived to be servant leaders. The definitive dimension of spirituality - living a faith relationship with the Transcendent that includes prayer or meditation - was not substantiated among the study group of 300 leaders and followers (p. 73).

The conclusions drawn in other research studies militate against the correlation between

the leadership dynamic and the spiritual dimension of leaders. Magnusen (2001), in a study involving 350 school personnel, suggests that there is little to no statistical correlation between the beliefs, action/styles, and characteristics of spiritual leaders and effective school leaders (p. 108). Rather, the research concluded there are several qualities that inversely described spiriutal and effective leader types in the study and "that spiritual leadership and effective school leadership stand in juxtaposition with one another" (p. 111). Similarly, Zwart (2000), determined that, when empircally tested, a link between spirituality and transformational leadership, using Bass and Avolio's (1989) Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire and Beazley's (1997) Spiritual Assesment Scale, was not evidenct among the 266 individuals in her study; contradicting earlier qualitative research. Strack (2001) reported only slightly more favorable results in associating spirituality and the leadership dynamic. In his study of 319 healthcare managers, Strack determined a "moderately positive correlation (r = .50) between the latent constructs of spirituality and leadership" (p. 98) Table 4 summarizes a selected number of research studies associating spirituality and leadership.

Table 4

Summary of Selected Research Studies Associating Spirituality and Leadership.

The collective results of the research studies thus far noted suggests a mutable

understanding in the relationship between the constructs of spirituality and leadership. Though the association remains unclear, a profusion of scholars have seized upon the early research of Marinoble (1990) and Jacobsen (1994) and have posited their own association between the leadership function and the phenomenon of personal spirituality. Among the bevy of scholars who have published works on spirituality and leadership - which in have turn led to the proffering of a spiritual leadership construct - Bolman and Deal (1995), Fairholm (1998), and Mitroff and Denton (1995) are representative of those who have contributed significantly to the discourse. Fairholm (1998) asserts that leadership theory and practice has evolved over the past 100 years through five levels of virtual reality ranged hierarchically on a continuum from managerial control to spiritual holism (p. xix). The five leadership environments include: leadership as management, leadership as excellent (good) management, values leadership, trust cultural leadership, and spiritual (whole-soul) leadership. Fairholm, drawing on the earlier research of Jacobsen (1994), identifies spiritual leadership as an emergent construct suggesting that followers are desirous of leadership behaviors that emanate from the leader's inner core spirit (p. xxii).

Integrating the many components of one's work and personal life into a comprehensive

system for managing the workplace defines the holistic or spiritual leadership approach. It sees the transformation of self, others, and the team as important, even critical. This new leadership reality is that of the servant leader. (Fairholm, 1998, p. 118)

Fairholm goes on to suggest that an individual's spirituality is inseparable from their

actions or disposition, thus drawing a direct link between a leader's sense of spirituality and the values and behaviors they exhibit in the workplace. These demonstrable values either enhance or detract from the creative milieu of the organization. "Spirituality is the source of our most powerful and personal values. When leader and led can share core spiritual values, such as faith, trust, honesty, justice, freedom, and caring in the workplace, a true metamorphosis occurs" (p. xxiii). In contrast to the scholarly context of Fairholm's work, Bolman and Deal (1995, 2001) address the relationship of spirituality and leadership in metaphorical terms.

Bolman and Deal (1995, 2001), using the literary devices of metaphor and parable, tell

the story of a dispirited leader searching for meaning in both his personal and business life. With the help of a mysterious protagonist, he migrates through a personal journey of self-discovery resulting in the eventual certitude that one's spirituality and leadership values are not bifurcated dimensions, rather, they are a single unified construct - spiritual leadership. Bolman and Deal, like Fairholm (1998), assert that the last decade of the twentieth century has been witness to a paradigm shift in the role of leaders and followers as each seeks to find a deeper and richer meaning in their personal and work lives. Bolman and Deal (2001) posit that workplaces "are devoid of meaning and purpose... with little regard for what human beings need in order to experience personal fulfillment" (p. 6). Fox (1994) echoes this sentiment and entreats the reader to associate one's spiritual life with one's livelihood.

Life and livelihood ought not to be separated but to flow from the same source, which is Spirit, for both life and livelihood are about Spirit. Spirit means life, and both life and livelihood are about living in depth, living with meaning, purpose, joy, and a sense of contribution to the greater community. A spirituality of work is about bringing life and livelihood back together again. (pp. 1-2).

Bolman and Deal (2001) suggest to the read that popular leadership practices and organizational thinking have neglected to suffuse the enduring spiritual elements of courage, personal faith, and hope throughout the organizational environment. In contrast, they suggest that recently introduced theories of leadership perpetuate the charismatic role of the heroic champion as leader, or that of the analytical skills of the technocrat, as preferred leadership characteristics. "Leaders who have lost touch with their own souls, who are confused and uncertain about their core values and beliefs invariably lose their way" (p. 11). According to Bolman and Deal, a disconnection between the functions of leadership and leader spirituality is a cause of organizational atrophy. This premise is shared by Mitroff and Denton (1995) in their seminal study of spirituality within corporate cultures.

In their work, A Spiritual Audit of Corporate America, Mitroff and Denton (1995) state:

The soul is precisely the deepest essence of what it means to be human. The soul is that which ties together and integrates the separate and various parts of a person; it is the base material, the underlying platform, that makes a person a human being. Unfortunately, rather than seeking ways to tie together and integrate the potential inherent in the soul with the realities of the workplace, most organizations go the opposite route. (p. 5)

This suggests that the recent corporate leadership debacles at Enron, WorldCom, Waste Management, Healthsouth, Anderson, and other business organizations are not merely aberrations but are reflective of the spiritual impoverishment of leadership which, in turn, gives rise to amoral, immoral, and unethical business conduct. Mitroff and Denton assert that it is precisely this lack of spiritual compass that is creating the current ethical pandemic in American business leadership. The necessary response to this leadership malaise, as posited by the authors, is an embracing of the spiritual dimension by leaders and their organizations. That is, recognize that by treating employees and organization as spiritual entities, leaders will not only fulfill deep-seated psychosocial needs of followers, but also enhance an organization's ability to achieve competitive advantage. Mitroff and Denton, based on the responses of 215 individuals made part of their research study, concluded that individuals who are employed by leaders and organizations they perceive to be spiritual are less fearful, less likely to compromise their values, can bring more of their creative intelligence to bear, and consider their organization as more successful (p. xiv). Drawing on the findings of their two-year study employing questionnaires and in-depth interview techniques, Mitroff and Denton present ten principle results of their research. Several of these principles are noteworthy in furthering this study's analysis of the relationship between spirituality and leadership. They include:

"Respondents were not in discord over their general definitions of spirituality." They

broadly defined spirituality as "the basic desire to find ultimate meaning and purpose in areas of life and to live an integrated life" (p. xv)

"The respondents overwhelmingly sought to integrate, rather than fragment, their

spiritual lives and their work lives' (p. xv)

"Finally, ambivalence and fear are two of the most important components of spirituality.

Contrary to conventional thinking, spirituality does not merely provide peace and settlement; it also profoundly unsettles" (p. xix).

This last point - the disquieting nature of spirituality in leaders and followers - is one that

Wheatley (2002) supports in her assertions on chaos and leadership. She comments, "no leader can create sufficient stability and equilibrium for people to feel secure and safe. Instead, as leaders, we must help people move into a relationship with uncertainty and chaos. The times have led leaders to a spiritual threshold" (pp. 21-21). Attempting to provide a context in which to examine the role of the spiritual dimension, Richards (1995) states that there are four domains that make up our being: the physical, the mental, the emotional, and the spiritual. These four "energies" are interdependent, one upon the other, where the absence of imbalance of one creates disharmony in our lives. Morris (1999) suggests a similar construct of the human experience, which comprises four aspects termed the aesthetic, the intellectual, the moral, and the spiritual. Mitroff and Denton (1995) operationalize these constructs by emphasizing the important role that the spiriutal dimension has in the lives of individuals and organizations. They propose that leaders and their organizations would be well served by embracing a non-threatening, non-dogmatic, yet spiritually integrated business culture. In turn, according to the authors, followers will feel a greater sense of fulfillment and wholeness in their personal, work, and spiritual lives, which will lead to greater efficiency and productivity at work. Conlin (1999) concurs and has reported that when organizations actively support the use of spiritual activities for their employees, productivity improves and turnover is less pervasive. The result is a synergystic union between follower and leader, thus benefiting each. This premise of unifying the interests of leaders and followers is consistent with Burns' (1978) notion of transforming leadership and his emphasis on the moral dimension of leading. It may also evoke the higher virtues of leaders and followers reaching out to wider social causes, or collectivities, which Burns inferred to be aspects of a transcending leadership phenomenon.

Several authors have voiced a note of caution in defining the essence of spirituality and

its relationship to the phenomena of leadership. Chaleff (1998) attempts to segregate the phenomenon of spirituality from religious dogma. He contends that spirituality is the acknowledgement of a "sacred element within one's self and within each living being" (p. 9) and from this awareness there emerges a commonality in core values among leaders who share the proclivity. He asserts that when vision and passion - characteristics which Chaleff views as apposite to the leadership dynamic - are imbued with sacred values, then spiritual leadership becomes manifest. Hicks (2002) offers a comprehensive analysis of the existing literature on spirituality and leadership and concluded, "the concept of spirituality is more disparate and contested than the current leadership literature acknowledges (p. 379). Harvey (2001) contends that the disparate collection of works on leadership and spirituality lacks focus and a rigorous, defined methodology. Camp (2002) voices caution in stipulating an a priori relationship between spirituality and leadership stating, "the convergence of leadership and spirituality promises enormous potential for good. Likewise, such a convergence has the same negative potential for evil. Spirituality, absent its moral moorings in the common good may lead to self-obsession or self-distortion" (p. 37). Similarly, Bailey (2001) cautions that associating spirituality with any leadership construct remains ephemeral and requires the benefit of additional structural examination (p. 368). This amalgam of opinion has resulted in the prestigious leadership journal, The Leadership Quarterly (2002), to call for professional papers intended to "examine the influence of spiritual leadership on organizational variables and refine the construct of spiritual leadership" (p. 843).

An association between spirituality and leadership has been the focus of great interest

among leadership scholars in recent years. Research studies (Beazley, 1997; Beazley, 2002; Isaacson, 2001; Jacobsen, 1994; Larkin, 1995; Magnusen, 2001; Marinoble, 1990; Strack, 2001; Trott, 1996; Zwart, 2000) have attempted to draw an a priori relationship between the two dimensions, resulting in mixed determinations. Concurrently, scholars have produced numerous texts extolling leaders to embrace the "whole person" of followers within the organizational environment resulting in the proffering of a spiritual leadership construct (Bhindi & Duignan, 1997; Bolman & Deal, 1995 and 2001; Blanchard, 1999; Block, 1996; Chaleff, 1998; Conger, 1994; Fairholm, 1998; Hagberg, 1994; Hawley, 1993; Herselbein, Goldsmith & Beckhard, 1996; Holmes-Ponder, Keyes, Hanley-Maxwell & Capper, 1999; Mitroff & Denton, 1995; Moxley, 2000; Ponder & Bell, 1999; Vaill, 1998). Though an abudance of literature exists on the nature of spiritually oriented leadership, there remains contention as to its meaning and definition.

Larkin's Proposition of a "Transcendent" Leadership Construct

Larkin (1994), one of the first to pursue an investigation of transcendent leadership in her

study, Beyond Self to Compassionate Healer: Transcendent Leadership, ascribes a spiritual dimension to the phenomenon. Expanding upon Marinoble's (1990) earlier research, Larkin (1994) sought to draw together "the strands of spiritual awareness with growth beyond self-centeredness" (p. 2) and extrapolates specific characteristics regarding the integration of the leadership practices and spiritual beliefs among transformational leaders. Larkin stipulates from the outset that her research is predicated upon a predetermined definition of a transcendent leader as "transformational leaders with the added dimension of being known for their effective leadership, their comfort with self and others, and their commitment to a spiritual awareness of God" (p. 65). Given this overt bias as the basis of her search - and the criteria used in the selection of her 14 study participants - Larkin sought to identify "key characteristics of individuals who act as spiritually oriented transformational (transcendent) leaders" (p. 73). Larkin's phenomenological research resulted in the identification of five invariant themes among the study participants. They included: God-centered confidence, empowerment, hospitality, compassion, and humility. Manifesting behaviors associated with the five invariant themes included: tolerance toward others, servant leadership behavior, acceptance, energy, celebration, honesty, spiritual awareness, wholeness empathy, I-thou functioning, openness to see beyond self, and surrender (pp. 119-121). Given Larkin's stipulated definition of a transcendent leader as one who is a transformational leader, with the added dimension of maintaining a commitment to a spiritual awareness of God, the findings of her study would be expected. That is, spiritually oriented leaders tend to exhibit spiritually oriented behaviors and characteristics. With this apparent bias in the study methodology, Larkin's (1994) claim that the emergent transcendent leadership construct is primarily a spiritual phenomenon would appear to be an intriguing, yet suspect assertion. Nevertheless, Larkin is certain in her assertion that spirituality is the basis of the transcendent leadership phenomenon. Supporting this notion, Sanders III, Hopkins, and Gregory (2003) posit that "transcendental" leadership is fundamentally rooted in the spiritual domain; consistent with Thompson's (2000) postulate that transcendent leadership cannot occur without spirituality.

In summary, building upon the previous works of scholars and researchers who have

associated spirituality and the leadership phenomenon, Larkin (1994) contends that transcendent leaders possess certain invariant characteristics and corresponding behaviors. These invariant characteristics include: a God-centered confidence, empowerment of others, hospitality, compassion and humility. Manifesting behaviors, which Larkin asserts are apposite to transcendent leaders include: tolerance toward others, servant leader behavior, acceptance, energy, celebration, honesty, spiritual awareness, wholeness, empathy, I-thou functioning, openness to see beyond self, and surrender. Larkin's assertion that transcendent leadership is a spiritually oriented construct may yet prove a viable claim. An examination by Aldon (1998) has sought an ontological understanding of the transcending leadership phenomenon where spirituality may reasonably be conflated with the dynamic of human consciousness.

Transcending Leadership as a Reflection of Human Conscious Evolution?

Background

Tangentially related to viewing the leadership dynamic from a spiritual orientation, the

works of several scholars who have opined on the evolution of human consciousness and societal development have been contextually linked by Aldon (1998) as a means of explaining the iterative nature of leadership theory and to suggest a basis for a transcendent leadership construct. Drawing prinicpally upon the works of Elgin (1993), Toffler & Toffler (1995), Wade (1996), and Wilber (1996), Aldon (1998) asserts that when leadership is examined from a metaphysical perspective the "essence" of the leadership phenomenon can be viewed as an evolving state of consciousness, or being. Conceptualizing the leadership phenomenon from a conscious evolution basis presents a unique contextual framework in which to examine past leadership constructs and project future paradigms - notably, the reasonableness of a transcending leadership construct. Prior to advancing Aldon's (1998) assertion that transcending leadership is fundamentally a reflection of human conscious evolution, it is instructive to consider the work of several authors who have contributed to this knowledge.

The word consciousness is used to embrace a panoply of meanings and associations -

mind, intelligence, reason, purpose, intention, awareness, the exercise of free will, and so on (Zohar, 1990, p. 220). Among the scholars who have contributed to this litany of meanings- and through their work, either knowingly or unwittingly, instigated an ontological dialogue of the leadership phenomenon - Chatterjee (1998), Donald (2001), Goswami (1993), Hubbard (1998), and Zohar (1990) are noteworthy. Chatterjee (1998) asserts that leadership is a pilgrimage of human consciousness and a search for the sacred in life (p. 199). Leadership is then an expression of harmony and synchronicity between a leader's virtuous beliefs and actions, which her terms integrity. Chatterjee posits that "the greatest challenge that faces leadership today is to be able to strike a balance between the sustenance of the entire context of an organization while nurturing individual identities" (p. 174). He suggests three laws of conscious leadership, which may positively respond to a leader's ability in achieving this balance. First, the law of complete concentration emphasizes the importance of cultivating mental focus and purity of though. The art of concentration is acquiring the capacity to withdraw one's consciousness from all things except the one, single goal toward which one is striving (p. 176). Chaterjee's second law of conscious leadership is the law of detached awareness, which asserts that by moving beyond thought to a state of unconditioned consciousness (p. 177) - through contemplation or meditation - a leader can enter a heightened state of awareness and attention and see the whole of a situation or experience more clearly. The law of detached awareness suggests that a leader enters a new plane of consciousness where silence brings clarity of purpose or action to the leader. "The greater the detachment of leaders from their thoughts, the greater is their access to pure awareness" (p. 178). The law of transcendence is Chatterjee's third law of conscious leadership. While Chatterjee's second law of detached awareness concerns "the world of the actual", his third law of transcendence postures the leader as a visionary who relates to "the world of the possible" (p. 178). Leadership is then operationalized as a conscious path designed to discover and propagate the innumerable talents, ambitions, and possibilities of followers. Chatterjee posits that leaders practice the law of transcendence by foregoing the impulse to hold on to possessions, addictions, and the desire for egocentric power (p. 180). He asserts that the essence of leadership is embodied in an amalgam of a leader's values and moral virtues, which inform the leaders response to situations and experiences - a phenomenon he refers to as actionable spirituality.

Associating spirituality with the nature of human consciousness is further explored in the

works of Goswami (1993), Hubbard (1998), and Zohar (1990). Zohar (1990), in her work on the phenomenon of human consciousness, asserts, "while consciousness is in many ways the most familiar and accessible thing that each of us possesses, it remains one of the least understood phenomena in this world" (p. 62). Unlike dualist philosophers who contend that the mind and body are separate and that there can never be any physical understanding of the "self" (consciousness), Zohar proffers a scientific explanation of human consciousness where mind and body conjoin - termed holism.

... if holism to have any real meaning, any teeth, it must be grounded in the actual physics of consciousness, in a physics that can underpin the unity of consciousness and relate it both to brain structure and to the common features of every day awareness. (p. 75)

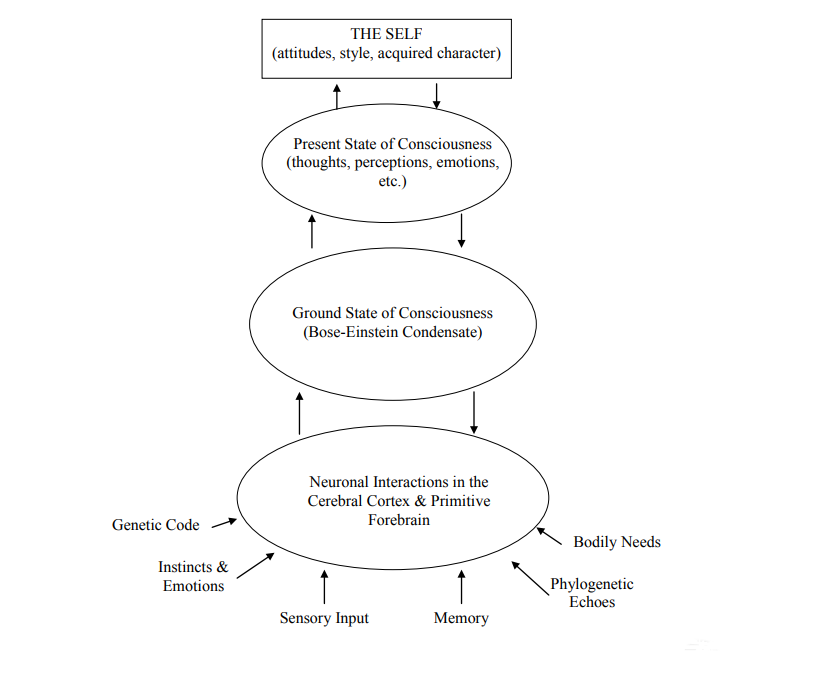

Zohar suggests a quantum mechanical model of consciousness manifest in the union

between two interacting systems: the computer like system of neurons which interact in the cerebral cortex and primitive forebrain to various stimuli, with an ordering and merging of various brain states (awareness) suggestive of the Bose-Einstein condensate (Bose & Einstein, 1924; Griffin, Snoke & Stringari, 1995). In biochemical terms, the Bose-Einstein condensate occurs when electronically charged molecules begin to vibrate in unison until they enfold so as to appear as one. Zohar (1990) applied this same principle in explaining the alignment of various brain states, or moments of conceptual awareness, in shaping consciousness, which Zohar terms the ground state of consciousness. Figure 4 depicts Zohar's (1990) conceptualization of the process of human consciousness; based on the principles of quantum mechanics and involving a complex interaction between the brain's neuronal activity and receiving stimuli.

Figure 4. Zohar's (1990) Quantum mechanic model of consciousness (holism). Source: Adapted from D. Zohar, The Quantum Self: Human Nature and Consciousness Defined by the New Physics, 1990.

Zohar's quantum mechanical model of consciousness suggests that individual neurons

may cause unconscious responses, such as breathing or blinking, but collective and synchronistic neuronal actions produce an electromagnetic field, which instigates the state of human awareness. Zohar's assertion is supported by the research of McFadden (2002) in which he posits that outside stimuli, passing through our sense, is channeled through the brain's electromagnetic field to neurons and then back to the electromagnetic field creating a self-referring loop that is the key to consciousness.

Broadening her scientific explanation of human consciousness, as a reflection of coherent

(ground state) neuronal impulses responding to internal and external stimuli within the cerebral cortex, Zohar (1990) proffers a preternatural genesis of consciousness, which embodies a spiritual dimension. In this regard she expands her "holism" assertions on consciousness, which embodies a spiritual dimension. In this regard she expands her "holism" assertions on consciousness from the quantum mechanical realm of the individual to a quantum vacuum model of consciousness, which unites the consciousness of the individual to the consciousness of the universe, and by extension, to an immanent God. Figure 5 reflects Zohar's quantum vacuum model of consciousness.

Figure 5. Zohar's (1990) Quantum Vacuum Model of Consciousness. Matter and forces emerge as fluctuations (excitation) in the vacuum, grow toward renewed coherence (Bose-Einstein condensate), and return to the vacuum as "enriched" fluctuations. Source: Adapted from D. Zohar. The Quantum Self: Human Nature and Consciousness Defined by the New Physics, 1990.

Accordng to Zohar, a viable world consciousness must conflate personal, societal, and spiritual dimensions into a unified whole. In doing so, the individual has access to an understanding of the nature of his existence, the relevance of man's relationship to Nature and others, and his relative place in the cosmos. Zohar asserts that human consciousness, as a physiological process within the brain, has evolved over epochs of time and awakened the human species to a nascent understanding that we are all inextricably linked to an immanent spiritual source - thereby unifying the science of human consciousness with its spiritual front. Congruent with Zohar's concept of "holism" - as an expression of a conjoined human consciousness/spirituality phenomenon - Gowami (1993) introduced the philosophy of monistic realism, which proffers a relationship between mind (consciousness), body (matter), and science (quantum physics).

In an effort to identify a bridge which could unify a spiritual source of human

consciousness with Cartesian dualism - where the world is compartmentalized into the "objective sphere of matter (the domain of science) and a subjective sphere of mind (the domain of religion)" (Goswami, 1993, p. 15) - Goswami (1993) proffered the concept of monistic realism. As noted by Goswami, the dualist philosophy originally espoused in the early works of the 17th Century French scientist and philosopher, René Descartes, summarily divided human existence of God and His suffused presence in the lives of men and Nature. As a reflection of the prevailing acceptance of Cartesian dualism, however, phenomena of matter has been broadly relegated to the world of science (i.e., scientific materialism) in association with five principles of classical physics: strong objectivity - "the notion that objects are independent and separate from the mind (or consciousness)" (Goswami, 1993, p. 15); casual determinism - "the idea that all motion can be predicted exactly, given the laws of motion and the initial condition on the objects" (p. 16); locality - that all objects travel through space with a finite velocity; material monism - a philosophic belief, rooted in scientific practice, that "all things in the world, including mind and consciousness, are made of matter" (p. 17); and epiphenomenalism - "the idea that mental phenomena and consciousness itself are secondary phenomena of matter and are reducible to material interactions" (p. 278). Goswami (1993) inverted the assertion of epiphenomenalism by suggesting that consciousness - the phenomena of mind - serves as the primary reality; a philosophy he terms monistic realism.

The antithesis of material realism is monistic realism. In this philosophy, consciousness,

not matter, is fundamental. Both the world of matter and the world of mental phenomena, such as thought, are determined by consciousness. Monistic realism posits a transcendent, archetypal realm of ideas as the source of material and mental phenomena. Thus, consciousness is the only ultimate reality (p. 48)

Goswami's use of the term "transcendent" in his defintion of monistic realism is

significant in that he ascribes the transcendent realm to an immanent God and later defines transcendental experience as a "direct experience of consciousness beyond ego" (p. 284). By asserting that consciousness (mind), and not matter, is the ultimate reality he posits a unifying world view which integrates the transcendent mind and spirit into quantum physics - an assertion synergistic with that of Zohar.

Suggestive of Zohar’s(1990) description of human consciousness as a physiological

(quantum mechanical model) dynamic, Donald (2001) contends that consciousness is a complex relationship between the neuronal activities of the brain and the stimuli it receives. He asserts that the human mind is a distributed cognitive network which is shaped by a symbolic web (culture) and it is through the collectivity of individual and societal experiences that consciousness has evolved over eons of time. Donald further asserts that man’s search for purpose, “is anchored in consciousness [but that] it can never be truly attributed to a single conscious mind, in isolation. It is the conscious mind in culture that contributes to the source of teleology in the affairs of the human world” (pp. 323-324). Donald builds upon Zohar’s (1990) quantum mechanical model of conscious development within individuals and extrapolates its physiological basis to societies, or cultures of individuals, over time. Donald (2001) asserts that a societal collective consciousness of Man is an evolving and ever expanding phenomenon incrementally building upon past cultural milieus, mores, values, and historical experiences. Donald intimates that the iterations of Man’s conscious development are miniscule when viewed in isolation, but when seen collectively the result is significant. He suggests an emerging nexus between Man’s cognitive development and conscious evolution that may propel the human species toward remarkable growth in intellectual capacity – resulting in significant advances in science and technology, literature and the arts, philosophy and existential thought, and human interactions. The latter of these – human interactions – harkens the conceptualization of new forms of leadership and followership theory. Whereas Donald expands upon Zohar’s (1990) quantum mechanical model of consciousness (holism) he carefully circumvents making any overt spiritual associations to conscious evolution. In contrast, Hubbard (1998) attempts to enrich Zohar’s (1990) quantum vacuum model in stipulating a cosmic consciousness manifest in a universal intelligence (i.e., God).

Hubbard (1998) offers a model of conscious evolution which progresses through five

great epochs leading to our current state of existence. The first epoch begins with the creation of the Universe, thought to be approximately 15 billion years ago. Hubbard, like Zohar (1990), ascribes the source of all existence to an immanent God, who set in motion the precise design that led to matter, life, self-reflective consciousness and mans awakening to the whole process of creation (Swimme & Berry, 1992). The formation of the solar system and Earth, approximately 4 ½ billion years ago, defines the second epoch. Hubbard (1998) suggests that in the third epoch, 3 ½ billion years ago, sentient consciousness emerged in single-cell objects of Nature as life sought to reproduce itself through cellular division. The fourth epoch, some hundreds of millions of years ago, is noted for a quantum leap from single-cell organisms to multicellular life and a concurrent leap in what Hubbard terms, present oriented consciousness. Multicellular organisms began to sexually reproduce by the joining of their genetic material and evolving into plants and animals. Through the act of procreation, an “awareness” of life beyond the single organism became manifest. The fifth epoch is identified with the emergence of human life and the beginnings of self-consciousness. Hubbard suggests that throughout the whole of human existence man has sought to understand himself in relation to others, Nature and the cosmos, and to his perception of a spiritual source(s). As a result, consciousness continues on a progressive path toward an emergent epoch termed universal humanity, which effortlessly blends “our spiritual, social, and scientific capacities” (p. 52). Universal humanity in turn advances a cosmic consciousness – man’s awareness that a universal intelligence animates every atom, molecule, and cell and that God is this universal intelligence, or eternal Presence. The manifestation of this Presence is the human Spirit or Self (p. 30). Hubbard’s conceptualization of conscious evolution as a progression evolving away from its spiritual source, over the epochs of time, while simultaneously returning to its cosmic origin is consistent with the writings of cultural philosophers Jean Gebser (1985) and Rudolph Steiner (1971) who proffered that the ultimate manifestation of consciousness is the preternatural unification of Man with his spiritual source. Similarly, Teilhard (1975) noted, “We have seen and admitted that evolution is an ascent towards consciousness. Therefore it should culminate forward in some sort of supreme consciousness” (p. 258). That is, much like a Möbius strip which loops back and around itself forming a single continuous edge, conscious evolution has now entered an epoch in which Man is paradoxically moving toward his archaic genesis. Figure 6 is a conceptualization of Hubbard’s (1998) model of conscious evolution.

Figure 6. Conceptualization of Hubbard's (1998) Model of Conscious Evolution. Arrow depicts progression of consciousness over five epochs of time suggesting future iterations of life and human awareness. Source: Adapted from B. M. Hubbard. Conscious Evolution, 1990.

Hubbard's (1998) conceptualization on the iterative nature of consciousness is aligned with the earlier work of Bucke (1969) who suggested that consciousness could be defined in three forms: simple consciousness, which is possessed by the upper half of the animal kingdom; self-consciousness, by virtue of which man becomes conscious of himself as a distinct entity apart from the rest of the universe; and cosmic consciousness which Bucke described as an intellectual illumination leading to moral exaltation and an awareness of immortality and eternal life.

While Hubbard (1998) examined conscious evolution in terms of an unfolding cosmos

and Zohar (1990) attempted to explain the physiological mechanisms of the brain inherent in conscious development, each suggested a preternatural genesis - or spiritual source. This spiritual wellspring, in turn, sparked the initial emergence of human consciousness and may yet be nurturing to new and richer dimensions of the phenomenon. Both authors intimate that as our collective human consciousness is deepened and enriched, so too will our tolerance and compassion for each other and Nature be enhanced. This growing awareness of our global relationship with each other and to Nature may then suggest new models of leading and following built upon collaboration and exchange relationships designed to satisfy mutual intrinsic, as well as extrinsic needs.

Aldon's Proposition of a "Transcendent" Leadership Construct

One such new model - transcendent leadership - has been proffered by Aldon (1998) in which she posits that the phenomenon is fundamentally rooted in the evolution of human consciousness. That is, as human beings continue to advance as a species we develop a deepened awareness of ourselves and our inextricable connection to others, Nature, and to a spiritual source. Aldon expands upon Burns (1978) definition of transforming leadership, where "people raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality" (p. 20), and posits transcendent leadership as a construct which "raises on another to higher levels of motivation, morality, and consciousness [thereby] co-creating the future in the essence of "spiritual humanism" (Aldon, 1998, p. 4). Spiritual humanism, a core element of Aldon's (1998) definition of transcendent leadership, is drawn from the work of Wilber (1997) who ascribes it to a metaphyiscal description where the essence of an individual is set in a deep spiritual context and made manifest in a spirit of community where values of trust, respect, love, and integrity are paramount. Aldon (1998) asserts that conscious evolution - reflecting the development of humankind over epochs of time - influences human interactions broadly and the manner in which leaders and followers interact, specifically. She then suggests a self-referral loop in the phenomenon where newly formed human relationship dynamics and leadership models instigate further enhancements in human consciousness; "... this author [Aldon] will urge the development of a leadership model that includes transcendence as an essential basic element. It is envisioned that such a model that is grounded in spiritual humanism can bring people to higher levels of consciousness" (p. 5). In essence, the evolution in human consciousness propagates new leadership constructs, which in turn support even higher levels of conscious evolution ultimately leading to spiritual humanism and the implied values and leadership behaviors of trust, respect, love, and personal integrity. Aldon integrates the putative theories of human conscious evolution of Elgin (1997), Wade (1996), and Wilber (1997) along with Toffler and Toffler's (1995) model of societal development. Table 5 offers a comparative depiction of the individual and societal stages of consciousness, as posited by Wade (1996), Wilber (1997), and Elgin (1993), along with Toffler and Toffler's (1995) striations of societal development.

Table 5

Comparative depiction of individual and societal models of human conscious evolution.

Source: Adapted from L. J. Aldon, Transcendent Leadership and the Evolution of Consciousness, 1998.

With the spectrum of consciousness theory depicted in Table 5 as her basis, Aldon (1998)

then posits a conceptualization in the evolution of leadership theory. She proffers that,

[leadership] theories are evolving a step behind the evolution of the individuals who created them. The movement from "great man" to trait/situational transactional [leadership] to collaborative/transforming leadership seems to be an outgrowth and improvement of what leadership practice previously prevailed. (pp. 73-74)

Figure 7 depicts Aldon's conceptualization of a unified societal evolution/conscious evolution/leadership evolution model proffering an emergent transcendent leadership construct.

Figure 7. Aldon's (1998) conceptualization of the evolution of leadership theory as a reflection of the evolution of human consciousness over the epochs of societal development. Source: Adapted from L. J. Aldon, Transcendent Leadership and the Evolution of Consciousness, 1998.

In summary, the evolution of the human conscious has been proffered by Aldon (1998) as

the integral basis for an emergent leadership theory she terms transcendent leadership. Aldon asserts that human consciousness, in its fullest and broadest sense, has developed along an evolutionary process from much simpler, very much more elementary forms of consciousness (Zohar, 1990, p. 220), so too has leadership theory and practice mirrored the progression of humankind. Where Larkin (1994) stipulated a fundamentally spiritual connotation to the prospective phenomenon of transcendent leadership from the outset of her study, Aldon (1998) approaches the construct seeking an ontological understanding. She ultimately determines that not only is the phenomenon of transcendent leadership a legitimate construct, but further, it is a logical reflection of conscious evolution as evidenced by societal and human development. Aldon (1998) then enriches her conscious-based theory of transcendent leadership by inserting a "spiritual humanism" (Wilber, 1997) dimension. This union intimates several behavioral factors associated with transcendent leaders - an attitude of trust toward followers and collaborators; respect for others and Nature; expressed love for people and the natural world; personal integrity, or moral character; and a spirit of community, in recognizing the interconnection and interdependence of Man's collective thought - or noosphere - stretching back to the beginning of global life (Aldon, 1998, p. 3).

The bases suggested by Larkin (1994) and Aldon (1998) in defining a transcendent

leadership construct are polemic in that both ascribe - either overtly or tangentially - a "spiritual" aspect to the leadership dynamic; an arguably subjective assertion. A more conformist explanation of the transcending leadership phenomenon has been proffered by Cardona (2000) who suggests that the essence of the phenomenon is rooted in extant Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory and manifest in an enhanced exchange relationship between leaders and followers; reminscent of servant leadership theory. Such an approach avoids the esoteric debate in associating a spiritual essence with the transcending leadership phenomenon.

Transcending Leadership as an Enhanced Exchange Relationship Construct?

Background

Conceptualizing the phenomenon of transcending leadership as a construct with an

implicit spiritual basis (Larkin, 1994) has been broadened by Aldon (1998) who describes transcendent leadership in monistic terms - as a construct conjoining spiritual humanism (Wilber, 1997) and the epochal evolution of human consciousness (Elgin, 1993; Toffler & Toffler, 1995; Wade, 1997). A third perspective on the essence of transcending leadership has been suggested by Cardona (2000), who deviates from the heretofore spiritually aligned bases. Cardona (2000) seeks to explain transcendental leadership in terms aligned with extant Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory (Dansereau, Graen & Haga, 1975; Graen, 1976; Graen & Cashman, 1975; Graen, Novak & Sommerkamp, 1982; Graen & Scandura, 1987; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1991; Graen & Wakabayashi, 1994) and Servant Leadership theory (Greenleaf, 1970). In associating leader-member exchange theory with servant leadership theory Cardona (2000) asserts that transcendental leadership is fundamentally an enhanced exchange relationship where "the transcendental leader adds to the transformational construct the spirit of service, and the development of this spirit in others (transcendent motivation)" (P. Cardona, personal communication, April 11, 2003). Prior to analyzing Cardona's (2000) proposition that transcendental leadership is fundamentally rooted in a dyadic partnership between leaders and followers - where a willful service to others is a defining characteristic - it is contextually useful to review the bases of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory and servant leadership theory.

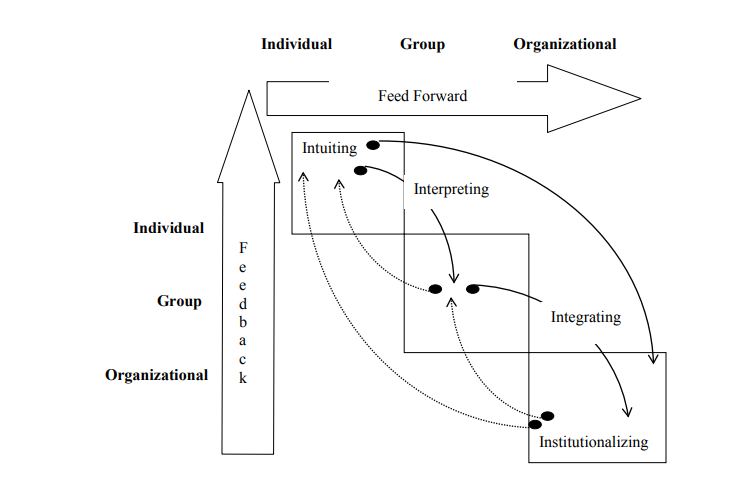

In contrast to viewing the leadership dynamic from the leader's perspective (e.g., trait or

behavior theories) or the follower and the context (e.g., situational-contingency theories), leader-member exchange (LMX) theory focuses on the dyadic relationship between a leader and followers (Northouse, 2001, p. 111) and the effect that this partnering has upon work group or organizational achievement. In this regard, LMX theory is unique within leadership research in that it establishes the dynamic relationship between leader and subordinates as the critical element of the leadership process (i.e., relational leadership). Originally conceptualized as the vertical dyadic linkage (VDL) model of leadership (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, 1975), and later as leader-member exchange theory (Graen, Novak, & Sommerkamp, 1982), LMX theory has progressed through four stages of development (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Figure 8 illustrates the evolution of the leader-member exchange theory as suggested by Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995).

Figure 8. Stages in development of Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory. Source: Adapted from G. B. Graen and M. Uhl-Bien, Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory of Leadership, 1995.

Stage One involved the early research of Dansereau, Graen, and Haga (1975) on work socialization resulting in the determination that supervisors developed widely varying relationships with their respective subordinates. Some subordinates reported a "high-quality social exchange" relationship with their supervisor, which was defined as a high degree of mutual trust, respect, and obligation - these employees were termed the "in-group". In contrast, other subordinates reported a "low-quality social exchange" relationship with their managers, reflective of a low degree of mutual trust, respect, and obligation - these subordinates were termed the "out-group" (Graen & Scandura, 1987). Stage One of LMX theory - or the vertical dyadic linkage (VDL) stage - asserted that leaders could not interact with followers uniformly (Graen & Cashman, 1975) because leaders had limited resources and time. As such, the social exchanges between the leader-follower, a two-way relationship, was determined as the unique premise and unit of analysis.

In Stage Two the terminology migrated from vertical dyad linkage (Dansereau et al.,

1975) to Leader-Member Exchange (LMX). Graen, Novak, and Sommerkamp (1982) expanded upon the notion that leaders do not maintain uniform exchange relationships with followers and asserted that high-quality social exchange relationships have a direct positive bearing on dyad and organizational performance. The converse is then implied for low-quality social exchange relationships. Sparrowe and Linden (1997) posit a similar position, asserting that strong ties between a leader and follower foster a relationship that builds loyalty, trust, mutual respect, and emotional attachment within the dyad. Stage Two moves beyond an understanding that different relationships between a leader and followers exist (i.e., VDL) to a discussion on how the dyadic relationships are formed and, consequently, the effects of the relationships on organizational performance. The implication is that when leaders and followers establish high-quality exchange relationships, positive organizational outcomes are enhanced.

Graen and Uhl-Bien (1991) are credited with conceptualizing Stage Three of LMX

theory, or the Leadership Making model. The Leadership Making model de-emphasizes the Stage One and Stage Two "in-group" and "out-group" social exchange relationship between a leader and follower(s) and accentuates the value of creating high-quality social exchange relationships with every follower, thus moving beyond the supervisor/subordinate relationship to one of a partnership relationship among the dyadic constituents. Graen and Uhl-Bien (1991) proffer a life cycle context to their Leadership Making model which suggests that individual dyads have the possibility of progressing through three states of relationship; the stranger state - consistent with the transactional leadership construct where exchange is predicated upon a formal relationship and subordination to the leader; the acquaintance state - where the social exchange relationship has not yet been formed into a partnership, but is somewhat more elevated than the "stranger" state; and, finally, the maturity, or partnership state - signifying a relationship of mutual elevation in trust, respect, and obligation. The maturity, or partnership state, is consistent with the characteristics espoused in the transforming leadership construct (Burns, 1978) where members of the dyadic group move beyond individual self-interests toward collective mutual interests (Graen and Uhl-Bien, 1995). The Leadership Making model (Stage Three) of LMX theory recognizes that in creating partnership relationships among all dyadic members the overall effectiveness and performance outcomes of the organization are enhanced. It additionally acknowledges that, although preferable, not all leader-follower (dyad) relationships will rise to the maturity (partnership) state. The essential element of the Leadership Making model, however, is that the leader earnestly offers and encourages each follower to enter into a high-quality social exchange.

In Stages One through Three, LMX theory development was foucsed on individual dyads

and the dyadic relationships between a leader and followers. Graen and Scandura (1987) conceptually broadened the understanding of how individual dyads form and support social exchange relationships. They extrapolated this knowledge to systems of interdependent dyadic relationships both within and external to the organization, thus asserting a forth stage of LMX theory. Graen and Scandura thus expanded the relevance and potenital of creating viable partnership relationships at work-unit levels, divisional levels, organizational levels, and inter-orgnaizational levels.

In summary, Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory is not broadly concerned about the

aspects of individual leadership or followership, per se. It is fundamentally interested in analyzing the relationship aspects which emenate between a leader and followers; referred to as relationship leadership (Komives, Lucas, & MacMahon, 1998). Leader-Member-Exchange (LMX) theory has evolved from the Vertical Dyadic Linkage (VDL) model, where high quality social exchange relationships (in-group) and low quality social exchange relationships within and external to work unit, divisional, and organizational levels. Establishing mature (partnership) social exchange relationships - the desirable end state of leader-member exchange - fosters a desire to satisfy the mutual interests of the dyadic member ahead of specific dyad or individual self interests (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). This inclination of "others before self" is consistent with tenets of servant leadership espoused by Greenleaf (1970).

Preceding the research of Dansereau, et al. (1975) on leader-follower exchange