"Expanding the transactional-transformative paradigm"

Leadership Research by

Dr. David A. Jordan

President, Seven Hills Foundation

Chapter Three

My basic idea of leadership is this: leadership is a matter of how to be, not how to do.

Frances Hesselbein (2002)

Methodology

Introduction

A fundamental feature of this study is to examine the "lived experiences" of individuals

perceived as transcendent leaders within a healthcare context and, in turn, seeks to elucidate the key characteristics exhibited by those individuals. By juxtaposing identified leadership characteristics of the study participants with those attributes generally associated with the transactional-transformational paradigm, fundamental or nuanced differences may present themselves. If discernible characteristic anomalies are noted, these attributes can then be triangulated with proffered propositions in the literature concerning a transcending leadership construct (Aldon, 1998; Cardona, 2000; Crossan, et al., 2002; and Larkin, 1994). Speculation may then be made as to the reasonableness of the construct as an iterative extension to the full range of leadership model (Bass and Avolio, 1994). Such as investigation warrants a qualitative approach using a phenomenological strategy of inquiry. The goal of phenomenological research is to reveal or extend significant new knowledge of human experiences through a participative methodology (Moustakas, 1994). The findings of phenomenological studies reflect the "thoughts, feelings, examples, ideas, and situations that portray what comprises an experience" (p. 47) and provides a foundation for reflection and further research.

This study seeks to describe the proffered construct of transcending leadership as

phenomenology. Leadership theory has demonstrated the propensity to evolve over time in response to various contextual factors and influences. Over the past 150 years, leadership paradigms have mutated through five families of leadership theory spawning various branches, or construct. Arguably, each new construct has contributed to a richer understanding of the leadership phenomenon and the effect it has upon interpersonal and intrapersonal relationships. The proposed new construct of transcending leadership seeks to contribute to the iterative nature of leadership theory and in doing so extend significantly our understanding of the human experience.

This chapter presents an overview and rationale for a phenomenological-qualitative

research design. Data collection strategies, explicitation (i.e., data analysis), interpretative protocols, and the role of the researcher are also discussed.

Strategy of Inquiry

Creswell (2003) identifies three normative approaches to research design: quantitative,

qualitative, and mixed methods. He notes that the quantitative approach is one in which the investigator uses post-positivist claims for developing knowledge, employs strategies such as experiments and surveys, and collects data on predetermined surveys. A qualitative approach is one in which the investigator relies upon constructivist perspectives such as narratives, phenomenologies, ethnographies, grounded theory studies, or case studies. Finally, the mixed methods approach involves data collection and gathering of numeric information as well as narrative information (pp. 18-20).

A phenomenological approach has certain characteristic advantages for the purposes of

this study. Phenomenological research provides an experiential and qualitative disclosure of the phenomena as perceived by the research participant (Van Kaam, 1966). Moustakas (1994) describes it as "a return to experience in order to obtain comprehensive descriptions that provide the basis for a reflective structural analysis that portrays the essence of the experiences" (p. 13). As noted by Rossman and Rallis (1998), qualitative research takes place in the natural setting of the individuals studied, it uses multiple methods that involve interaction between the researcher and subjects, it is emergent rather than tightly prefigured, it is fundamentally interpretive, and the qualitative research views social phenomena holistically.

This study utilizes the oral descriptions of the leadership experience by study participants

and corroborators as a means of reflecting upon the central questions of the research:

R1. What are the key characteristics of healthcare professionals who are perceived to be

transcendent leaders?

R2. Do the key characteristics evidenced by healthcare professionals, perceived as

transcendent leaders, differ from those of transactional and transformational leaders as stipulated by Burns (1978) transactional-transformational paradigm and Bass and Avolio's (1994) full range of leadership model?

R3. Is it reasonable to propose a transcending leadership construct?

The relative dearth of literature and rigorous inquiry on the phenomenon of transcending leadership has stifled any definitive response to these questions and, as such, this study potentially represents a new body of knowledge.

Research Design

Researcher's Role

Mertens (2003) notes that the qualitative researcher systemically reflects on who he or

she is in the inquiry and is sensitive to his or her personal biography and how it shapes the study. This introspection and acknowledgement of biases, values, and interests typifies qualitative research (In Creswell, 2003, p. 182). Likewise, the investigator's contribution to the research setting can be eminently valuable, rather than detrimental (Locke et al., 2000). My own experiences as a healthcare executive extend from 1973 to the present. During those years, I have observed and worked closely with a select number of individuals I would tacitly identify as evidencing transcending leadership behaviors, given the tentative definition as evidencing transcending leadership behaviors, given the tentative definition proffered in Chapter 1. These individuals possessed remarkable abilities in motivating their collaborators to reach extraordinary standards of performance and, further, they inspired colleagues to be of service to individuals and causes beyond the boundaries of the organization in which they were a part. These notable characteristics were obvious and compelling as seen from the collaborator perspective.

Given my past health management experiences, I acknowledge the potential of certain

biases in this study. As part of the data collection and analysis procedures, every effort was made to ensure objectivity, including the phenomenological techniques of epoche and bracketing (Patton, 1990, p. 407). A reflexive methodology suggested by Alversson and Sköldberg (2000) was also made part of the research methodology as a means of enhancing the internal trustworthiness of the study. These techniques are more fully disclosed in the data analysis section of this chapter. Findlay and Li (1999) assert that the theoretical position a researcher holders about the nature of existence (ontology) and the philosophies of knowledge that he or she embraces (epistemology) are inextricably related to the methods adopted in the pursuit of knowledge. As such, particular care was given in the design of the research methodology employed in this study.

Selection of Participants

In keeping with Creswell's (1998) assertion that a phenomenological study include

"interviews with up to ten people" (pp. 65 & 113) and Boyd's (2001) claim that two to ten research subjects are sufficient to reach saturation, this study incorporates a sampling of fourteen participant healthcare leaders identified by expert nominators from across the United States. The nominations were based on the tacit definition of transcending leadership presented in Chapter 1. Additionally, two individuals chosen by the researcher were identified to participate in a preliminary pilot study. The expert nominators were the chief executive officers of State Hospital Associations (n=45) and State Medical Societies (n=49). The chief executives of State Hospital Associations and Medical Societies are considered to be intimately familiar with healthcare leaders within their membership who would potentially exemplify the proffered definition of a transcendent leader (See Appendix E: Expert Nominator Solicitation Letter).

In total, 126 transcendent leader nominations were received representing 21 states. After

soliciting their interest and consent to participant in the study, (Appendix F: Transcendent Leader (Nominee) Solicitation Letter), 82 perceived transcendent healthcare leaders ultimately affirmed their willingness to be part of the final research. The first seven nominated physician-leaders and seven hospital/health system leaders who confirmed their willingness to be part of the study by agreeing to the terms set forth in the "Consent to Participate Form" (Appendix G) were deemed study participants. A biographical and organizational synopsis of each participant is offered in Appendix H (Study Participant Background and Organizational Context). The involvement of the two pilot study participants was limited to assisting the researcher to practice using the interview guides. Their comments and responses to the interview questions were not made part of the final research findings.

This study utilizes a relatively small, non-representative sampling of healthcare leaders in

the United States and nonsystematic data gathering techniques involving retrospective self-reports obtained in semi-structured interviews. Corroborative data, involving reports from others who were professionally familiar with the study participants, were intended to add to the credibility of the qualitative (phenomenological) study (Chemers, 1997, p. 82).

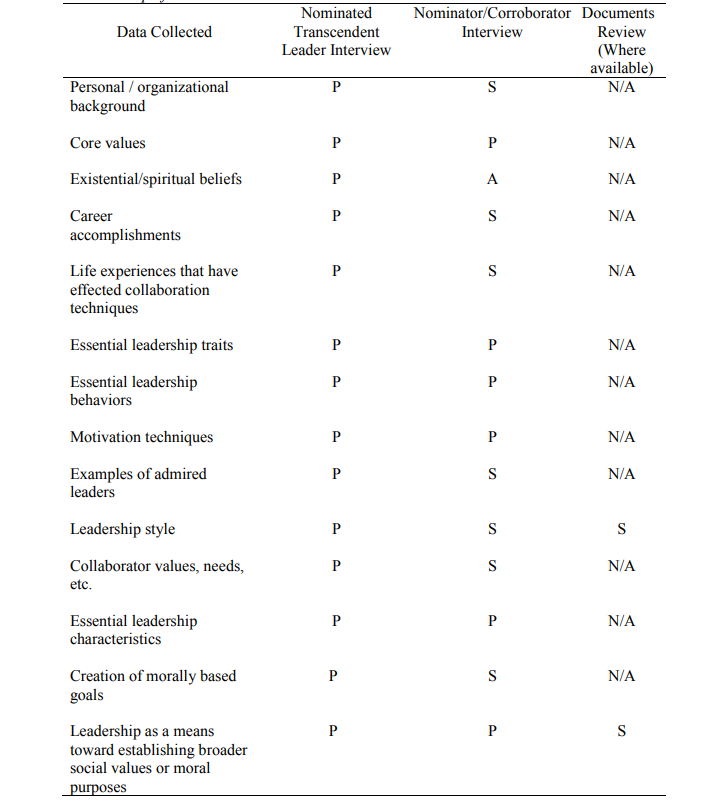

In order to satisfy the need to corroborate the self-reported experiences of the study participants, the expert nominators were also included a telephone interview regimen. Where available, a review of available personal writings and other documents from study participants were examined as a further corroborative device (Table 12: Relationship of research methods to data collection).

Data Collection

Bogdan and Biklen (1992) suggest four data collection types for qualitative research.

These include direct observations, interviews, document review, and use of audiovisual materials. Interviewing has the advantage of use when participants cannot be observed directly. Alternatively, its limitations include the fact that not all individuals are equally articulate in telephone interviews and the researcher does not interact personally with participants in their natural settings, which could serve to limit the rich depiction of data collected. However, corroborating interviews, personal writings, organizational reports, and other written materials served as a method to obviate these shortcomings. A telephone interview data collection method appeared to be most reasonable, due to geographic distances between the principal investigator and the study participants and expert nominators (corroborators).

The study participant interviews and corroborator interviews last between 60 and 90

minutes each, following the broad themes set forth in the "Interview Guide for Nominated Transcendent Leaders" (Appendix I) and "Corroborator Interview Guide" (Appendix J).

Table 12

Relationship of Research Methods to Data Collection

(Note: P = primary source; S = secondary source).

The study participants and corroborator interview guides consisted of 14 and 15,

respectively, open-ended, semi-structured research questions designed to draw each respondent into a narrative dialogue, or story-telling experience, concerning their lived experiences as leaders in the healthcare community. Although interview guides were used as the framework of discussion, care was given to allow the dialogue to follow and explore emergent themes beyond the boundaries of the guide. This process is consistent with the phenomenological approach and its aspiration to examine the lived experiences of research subjects.

The sequence of interviews - study participant followed by corroborator - was intended to

establish an ethnographic understanding of the study participants as seen through the eyes and experiences of the corroborating nominator. This process enriched the interview process and suggested emergent aspects about the study participant, which may have not have surfaced otherwise. Throughout the interviews, restatement and alternative questioning techniques were used to clarify responses.

Each of the interviews was tape-recorded and transcriptions were then prepared for

preliminary analysis of significant statements (clusters and categories), and the generation of meaning units (themes and invariant themes). Summaries of the interview themes were then forwarded to each study participant for member check purposes. Any corrections or amendments made by the study participants were incorporated into a final summary.

Pilot Study

As noted in the "Selection of Participants" section, a pilot study was undertaken. The

purpose of the pilot study was to determine the relative value of the questions posed in the study participant interview guide, to practice using the guide, and to become comfortable with the techniques of the interpretive approach to qualitative interviewing (Rubin and Rubin, 1995). The pilot study participants were purposefully selected to reflect the professional backgrounds of the targeted study participants; that is, a physician-leader, and a hospital/health system leader. The initial interview and preliminary analysis phases of the pilot study allowed the researcher to practice the data analysis techniques of epoche, bracketing, and related methods more fully discussed in the data analysis and interpretation section of this chapter.

Each of the pilot study interviews were conducted prior to the start of the main body of

interviews. Critical comments and suggestions for improvements to the interview guide and the interpretive approach were solicited of the pilot study participants.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Psathas (1973) asserts that, "Phenomenological inquiry begins with silence" (In Bogdan

and Biklen, 1992, p. 34). This silence is an attempt to grasp what it is that is being studied. "What phenomenologists emphasize then is the subjective aspect of people's behavior. They attempt to gain entry into the conceptual work of their subjects" (p. 34). Creswell (1998) notes that "phenomenological data analysis proceeds through the methodology of reduction, the analysis of specific statements and themes, and a search for all possible meanings" (p. 52). Creswell explains the qualitative approach to study design:

The process of data analysis involves making sense out of text and image data. It

involves preparing the data for analysis, conducting different analyses, moving deeper and deeper into understanding the data, representing the data, and making an interpretation of the larger meaning of the data. (Creswell, 2003, p. 190)

Two approaches of data analysis and interpretation were considered for this study. The

first is a methodology described by Patton (1990) involving the aspects of epoche, bracketing, horizontalization, identification of invariant themes, and structural synthesis. The second alternative approach considered was one posited by Creswell (2003), which involves six steps - organizing data, reading through the data to gain a general sense of its overall meaning, coding the data, describing categories or themes, advancing how the description of themes will be represented, and making an interpretation of the data (pp. 191-204). The data analysis methodology employed in this study was intended to incorporate certain aspects of each approach, specifically.

1. Epoche: Eliminating a researcher's personal bias prior to the start of a research study is

a fundamental prerequisite for trustworthiness within a phenomenological study. Epoche is a "phenomenological attitude shift" intended to remove, as much as possible, researcher bias toward the subject matter (Patton, 1990, p. 407). To that end, I attempted to suspend any preconceived notions that I had of transcendent leader behavior, as identified in the Researcher's Role section of this chapter.

2. Bracketing: Bracketing involves a conscious awareness on the part of the researcher to

maintain an open and trustworthy attitude during the actual interview, data collection, analysis, and interpretation phases. "In bracketing, the subject matter is confronted, as much as possible on its own terms" (Patton, 1990, p. 407). This was accomplished by attending to the notion set for by Psathas (1973): "Phenomenological inquiry begins with silence" (In Bogdan and Biklen, 1992, p. 34). That is, I attempted to listen first to the subject and accepted his or her opinions and comments as presented.

3. Organize and prepare the data for analysis (Creswell, 2003, p. 191): Hyener (1999)

calls upon the researcher to listen repeatedly to the taped recording of each study participant in order to become intimately familiar with the voice of the interviewer. Zinker (1978) reminds the reader that the term "phenomenology" implies a process, emphasizing the gestalt, or holistic sense, the research participant experiences. Greenwald (2004) adds, "the here and now dimensions of those personal experiences give phenomena existential immediacy" (p. 18).

Upon completing each interview in this study, the audiotapes were immediately

transcribed, repeatedly listened to, and the process of analyzing data for "meaningful clusters" (Patton, 1990, p. 408) or "chunks" (Rossman & Rallis, 1998, p. 171) was begun.

4. Identification of themes: Qualitative software (i.e., QSR N6-NUD*IST; Non-numerical

Unstructured Data Indexing Searching and Theorizing) was used to content code the study participant transcriptions and to analyze the emergent patterns and themes. Twelve "parent nodes", reflecting 12 categories of data, were created by coding the transcript data for each interview question. The transcript data for each of the study participant responses was then examined to extract all variables noted. These variables were compared across all 14 participating leader responses in each category of data as a means of identifying discrete variables; that is, variables which when combined were considered to be unique themselves. For example, in the category of data concerned with essential leader behavior, the state variable of "shows humility in his actions" and "is humble" were determined to have a common meaning and therefore grouped together as the discrete variable termed "humility". Unique variables were interpretively grouped by the researcher into categorical themes - or "child nodes" - within the qualitative software.

This stage of the data analysis suggest an iterative process, in that categorical themes of

the interview data from each of the study participant transcripts were regrouped and organized until a few significant themes remained. Once a summary for each category of data was completed, all twelve summaries, reflecting the responses of the 14 study participants, were juxtaposed and analyzed to determine any broad patterns or invariant themes (Patton, 1990, p. 408) which could inform the three research questions pertinent to this study. The researcher looks "for the themes common to most of all of the interviews, as well as the individual variations" (Hyener, 1995, p. 154) while judicious thought it given to avoiding the cluster of themes if significant differences exist. However, unique or minority views expressed by the study participants were considered valued counterpoints (Groenewald, 2004, p. 21) and served to further enrich the findings presented in Chapter 4.

5. Interpret the meaning of the data: Consistent with Patton's (1990) structural-synthesis

phase (p. 409), Creswell (2003) suggests a final step in data analysis, which involves interpretation of the relational themes (p. 194). During this final step in data analysis and interpretation, the invariant themes distilled from the study participants were consolidated and synthesized to discern the rich meanings shared by all respondents. It is here that the researcher "transforms participants everyday expressions into expressions appropriate to the scientific discourse supporting the research" (Sadala and Adorno, 2001, p. 289). Coffey and Atkinson (1996) underscore that "good research is not generated by rigorous data alone ... [but] 'going beyond' the data to develop ideas" (p. 139). Generalizations or initial theorizing, however modest, is borne from the qualitative data (Groenewald, 2004, p. 21). The data collection and data analysis processes employed in this study were judiciously reviewed to confirm the logic of the procedural steps. This procedural review included: how "meaningful clusters", or categories of data, were crafted from conversations with the research subjects, how the data was organized and themes identified within each of the categories, methods used to identify inter and intraindividual significant or invariant themes, and finally, the approach enlisted to articulate a broad essence description across all categories of data and participants.

Table 13 illustrates the methodological framework employed in this study. The approach

is inductive and consistent with qualitative-phenomenological research.

Table 13

The research methodology employed in this study of perceived transcendent leaders.

Ensuring Trustworthiness and Credibility

In order to enhance the credibility of qualitative data using a phenomenological strategy

of inquiry, a number of methods can be employed including triangulation, member checking, and peer debriefing (Creswell, 2003). Alvesson and Sköldberg (2000) ascribe to qualitative research the additional requirement of researcher reflexivity. Reflexivity involves self-inquiry and an examination of the assumptions guiding the research. To ensure trustworthiness in this study of the lived experiences of perceived transcendent healthcare leaders, the following strategies were employed:

1. Triangulation: Denzin and Lincoln (2000) note the usefulness of triangulating data

from a variety of sources and techniques as a means of building credibility for the research findings. Prestera (2004) notes that, "triangulation can be used not only with data collection techniques and data sources, but also with the investigators and theories (exploring the data through the lens of multiple theories and perspectives)" (p. 3). In this study, extant literature on the key characteristics of transformational and transactional leadership theory are compared to the invariant themes and essence descriptions generated by the study participants and their corroborators. Similarities and distinct differences were then noted and juxtaposed to the propositions put forth in the review of the literature concerning the transcending leadership phenomenon. Figure 11 illustrates the triangulation methodology employed in this study.

Figure 11. Triangulation of extant transactional-transformational theory and proffered transcending leadership propositions with results of phenomenological inquiry.

2. Member Checking: A further method of enhancing the credibility of the qualitative

research is to have study participants review the researchers interpretations of their comments. This allows the study participant to clarify and, if needed, revise their earlier statements. In this study, each participant received an interpretive summary of their comments as presented during the interview process. Opportunity was offered to each study participant to clarify or modify these interpretations prior to beginning the analysis of data.

3. Peer Examination: Whereas member checking involves participants reviewing the

research's work, peer examination involves fellow researchers reviewing the work of the researcher. This serves as another method toward improving the credibility and quality of the research undertaken. This study incorporated two individuals, acting as peer examiners, who had previously completed the requirements of the Doctorate of Healthcare Administration within the Department of Health Administration & Policy at the Medical University of South Carolina. These individuals were solicited to ask probing questions concerning the research methodology and examined the findings of the research for reasonableness.

4. Reflexivity: Kabut-Zinn states that "inquiry doesn't mean looking for [predetermined]

answers" (In Bentz and Shapiro, 1998, p. 39). As such, reflexivity involves identifying the "Interrelationships between the sets of [personal] assumptions, biases, and perspectives that underpin different facets of the research" (Weber, 2003, p. vi). Reflexive research underscores the need for honest researcher introspection concerning beliefs, which could be ultimately detrimental to the credibility of the research design, including the interpretation of data. Weber (2003) states:

In short, when we try to understand the assumptions, biases, and perspectives that underlie one component of our research... we are being reflective. Insofar as we try to understand the assumptions, biases, and perspectives that underlie all components of our research and, in particular, the interrelationships among them, we are being reflexive (p. vi).

As a means of assuring an adequacy of reflexive consideration, the principle researcher

of this study initiated a reflexive methodology suggested by Alvesson and Sköldberg (2000). This methodology involved the mindful awareness of four elements:

"1. Systematics and techniques in research procedures: There must be a logic in the way

the researcher collects and interacts with the empirical material.

2. Clarification of the primacy of interpretation: The researcher acknowledges the

primacy of interpretation, which implies that research cannot be disengaged from either theory or self-reflection.

3. Awareness of the political-ideological character of research: What is explored and

how it is explored, cannot but support or challenge some values and interests in the society. The political and ideological aspects of research must therefore be acknowledged.

4. Reflection in the relation to the problem of representation and authority: There are

problems of representation and authority connected to any research... and the relationships between [researcher and study participants] and the world need to be examined." (In Stige, 2002, p. 5).

Alvesson and Sköldberg (2000) assert that reflexivity in qualitative research involves the search for a balance among these four perspectives.

To ensure that an acceptable balance between the perspectives suggested by Alvesson and

Sköldberg were achieved in this study, Thomas Kent, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Management at the College of Charleston (SC), served as my reflexivity mentor. Dr. Kent brought to this study a substantial background in leadership scholarship and proved invaluable in considering the logic of my methodology and the primacy of allowing data interpretation to reflect the "voice" of the study participant and not my own (Appendix K: Reflexivity Mentor Interview Guide).

5. Expert External Examiner: As distinct from the peer examiner, the external examiner

offers an overall "assessment of the research project [either] throughout the process of research, or at the conclusion of the study" (Creswell, 2003, p. 197). The expert examiner contributes to the "trustworthiness", "authenticity", and "credibility" of the research topic (p. 196) by reviewing the research project for coherency in design and speculates on the studies overall prospective contribution to the body of knowledge. Noted leadership theory scholar and author, Gilbert W. Fairholm, DPA, Emeritus Professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, served as the expert external examiner for this study (Appendix L: Expert External Examiner's Report). The insight and suggestions offered by Dr. Fairholm were uniquely valuable in considering the leadership phenomenon being studied.

Study Limitations

This study may have several limitations. First, although corroborators are an integral part

of the research design, the individuals serving in this capacity were also the nominators of the transcendent leader study participants. This may have produced a favorably biased opinion of the study participant by the corroborator. A more validating dimension to the research design would involve seeking corroborative testimony from a number of individuals working both as peers, subordinates, and superordinates of the nominated study participant. However, logistics involving the geographic disparities and schedules between study participants and additional corroborators precluded this, warranting a more comprehensive approach in any future study design. Secondly, this study involved only individuals who hold key executive roles within their respective work group or organization. This precluded the study of individuals among the strata of employees who might also be perceived as transcendent in their leadership behaviors. Third, the individuals who acted as study participants were those who agreed to engage in the research. Others, who were nominated and chose not to participate, may have expressed significantly divergent themes and opinions. Fourth, the applicability of the signficant themes and essences of a transcending leadership construct derived in this study may have limited applicability outside of the sample of study participants since a normative definition of transcending leadership (transcendent leaders) has yet to be fully established in the literature. Fifth, the research design relies on the use of telephone interviews as the principal data collection type. A more rich depiction of the phenomenon, as seen through the experiences of the study participants, would involve a face-to-face data collection protocol within the study participant's natural environment.

Protection of Human Subjects

On February 14, 2003, an Exempt Research/Quality Assessment Review Application was

submitted to the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Institutional Review Board (IRB) for approval to proceed with this research study (Appendix K). The investigator was notified by electronic mail on February 19, 2003, that the application to conduct "A Phenomenological Study of Transcendent Leaders in Healthcare" was approved.

Conclusion

Chapter 3 presented the theoretical framework for the research methodology and design

used in this study of transcending leadership and transcendent leaders. Due to the emerging nature of this phenomenon, no stipulated definition yet exists and, therefore, the integration of Burns' 1978 meager commentary on transcending leadership coupled with his assertions on moral leadership was proferred as the basis from which to examine the lived experiences of perceived transcendent healthcare leaders. Fourteen study participants with a corresponding number of corroborating interviewees from 12 geographically diverse states made up the study. A data analysis and interpretation process incorporating methodologies suggested by Patton (1990) and Creswell (2003) were utilized as a means of identifying invariant themes evidenced by the study participants. A reflexivity methodology was employed to explore and bracket researcher bias, while methods utilized to enhance credibility and trustworthiness of the findings included the strategies of triangulation, member checking, the use of peer examiners, and the engagement of an expert external examiner.

A descriptive examination of the leadership experience as evidenced in the lives of the

study participants is presented in Chapter 4.